Has Deleuze left the Theory of Architecture?

“Has Deleuze left the Theory of Architecture? Ignasi de Solà-Morales, the influence of Gilles Deleuze in the Theory of Architecture and its contemporary inscription” is an article published on Viceversa: Theorem: Discourse(s), edited by Giacomo Pala. Pala invited me to select an excerpt from a relevant work by a theoretical architect from the last decades. I chose Ignasi de Solà-Morales, selecting two excerpts from the essays published after the Any Conferences Series. This issue of Viceversa magazine intended to be an Anthology of Theory of Architecture, establishing links between generations of architectural theorists.

Image credits: A Peach Tree, October 2000, Joel Sternfeld. Courtesy of the artist.

Excerpt I

“When architecture and urban design project their desire onto a vacant space, a terrain vague, they seem incapable of doing anything other than introducing violent transformations, changing estrangement into citizenship, and striving at all costs to dissolve uncontaminated magic of the obsolete in the realism of efficacy. To employ a terminology current in the aesthetics underlying Gilles Deleuze’s thinking, architecture is forever on the side of forms, of the distant, of the optical and the figurative, while the divided individual of the contemporary city looks for forces instead of forms, for the incorporated instead of the distant, for the haptic instead of the optic, the rhizomatic instead of the figurative.

Our culture detests the monument of the one and the same. Only an architecture of dualism, of the difference of discontinuity installs within the continuity of time, can stand up against the anguished aggression of technological reason, telematic universalism, cybernetic totalitarianism, and egalitarian and homogenizing terror.”

Ignasi de Solà-Morales, “Terrain Vague.” (1)

Excerpt II

“Deleuze and Guattari propose a fragmentary theory of the body and of the productive flows to which the body gives rise in order to explain the relationship that links the productive energies of late capitalism. In the capitalist body without organs there is no longer any possibility that the body can provide support for a space from which to inscribe the rituals of initiation and exchange characteristic of primitive societies. The permanence of operations in which gestures and words (assigned to bodies) responds only to a deliberate resistance to capitalist dissolution, formed from a new archaism that leads our society and its bodies without organs to seek everlasting signifiers in primitive words and gestures.

For Deleuze and Guattari, however, the body in late capitalism is, in its totality, constantly territorialized by the abstract flow of numbers, money, and the market. Only a schizo-economy of diversification maintains the presence of signs which remain as signals of desire. In this post-humanist diagnosis, there is nothing left of the supposed unity of bodies nor of their permanence; all that remains is traces of their production transformed into signs that, as they continue to circulate, constitute nodes of reterritorialization in a permanent state of exchange of desires transformed into fluctuating commodities. […]

Only an art and an architecture that recognize the precariousness of bodies and their objectivized fragmentation, along with the persistent dynamism and energy that nonetheless continue to circulate in them, are capable of presenting a convincing discourse at the present moment.”

Ignasi de Solà-Morales, “Absent Bodies.” (2)

Ignasi de Solà-Morales was born in Barcelona in 1942 and died prematurely in Amsterdam in the year 2000. He was majorly known as an architect and Professor at ETSAB (Cataluña’s main architecture school), having also taught at the universities of Princeton, Columbia, Turin, and Cambridge, among others. Moreover, Solà-Morales also held a diploma in Philosophy, having taught Aesthetics at the University of Barcelona between 1970 and 1973. His double training and unique methodology distinguished him from most of the architects that tend to incorporate philosophical knowledge into their theoretical incursions however based on autodidactic approaches. The result was a theoretical work and a rare example of what we may consider being at the foundations of the contemporary theory of architecture, notwithstanding relying on continuity and tradition. The exercise of the theory of architecture has always been transversal. Drawing, painting, sculpture, narrative, even in its most fictional forms, have always been an indivisible part of the most important architectural theories from Vitruvius to Alberti, Ledoux to Tafuri without putting into question the core of architecture or of what might be fundamental to the discipline. Undoubtedly due to his rare educational ground, Solà-Morales was able to establish transversal links, not only between architecture and philosophy, but also between the different artistic practices and various cultural fields of production, from photography to cinema and the visual arts, in order to think about the contemporary city (the metropolis) through its representations, or even through the knowledge of other exterior disciplines whose contributions might be as important to map our present condition, such as politics, economics or natural sciences. Updating and revitalising a tradition that seemed forgotten in the theory of architecture, where does the novelty introduced by Solà-Morales reside? And has it survived until today considering that a theory presupposes a work that persists beyond its conditions of production allowing for new inscriptions in the present state of architectural theory? Are the “prescriptions” by Solà-Morales for the contemporary architecture (the last paragraph of each excerpt) still valid?

The excerpts presented here come from two different essays written by Solà-Morales for the Any Conferences. From 1991 to 2000, each year in a different city around the world, multidisciplinary and cross-cultural conferences on the current state of architecture were held, bringing together architects, artists, philosophers, historians, sociologists, among others from many different disciplines, and from which most of the contemporary theoretical work on architecture was born. Solà-Morales had a key role in the organisation and he was an assiduous presence through all conferences. The proceedings were then published in a homonymous books (many of them currently sold out) and in the case of Solà-Morales’ essays collected in books of his own, published in several languages including his native Spanish. The two chosen essays appear in the book Territorios, published by Gustavo Gili, in 2002, two years after his death. The first excerpt belongs to the original essay “Terrain Vague” presented at the Anyplace Conference in 1994, whereas the second is part of the essay “Absent Bodies” presented at the Anybody Conference in 1996. In both essays, we witness Solà-Morales’ constellation of references and how he carefully weaves them to form what we may define as a multiplicity to borrow the concept from Gilles Deleuze, the French philosopher much admired by Solà-Morales. A multiplicity (multiplicité) is a singular unity composed of heterogeneous elements that contribute to the multiplicity’s indivisibility and unique expression. It differs from the Multiple which, as the proper name says, can be multiplied or divided ad infinitum, as it also differs from the One that is formed or composed by elements of the same nature, order, material, etc. In this sense, Solà-Morales’ theories present multiplicities since for him it was only possible to understand the contemporary condition of the metropolis and of its inhabitants resorting to examples spanning from different contexts, epochs, authors, styles, etc., resembling Deleuze’s own method. During those years, Deleuze’s work, as well as his work with Félix Guattari, was a major influence on several participants at the Any Conferences and not only to Solà-Morales (Elizabeth Grosz, John Rajchman, Brian Massumi - whom later had translated Mille Plateaux into English - Greg Lynn, among many others), however the translations of his philosophical thought and concepts into architectural language and theory proved, in our point of view, to be extremely problematic.

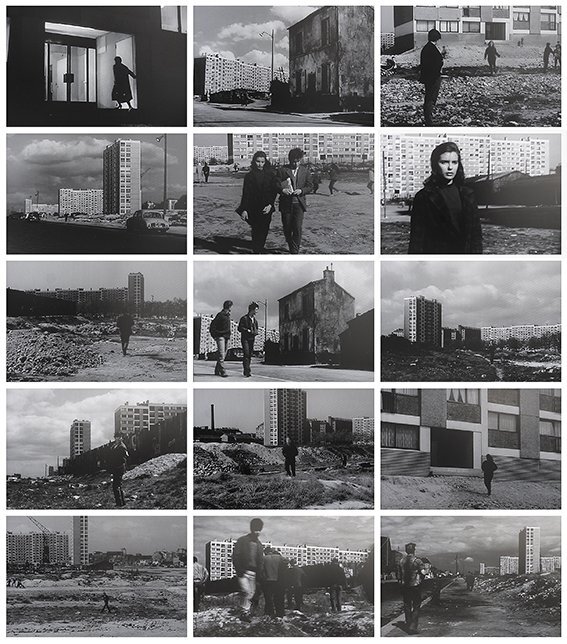

Stills from Terrain Vague, Marcel Carné, 1960

In the first essay, we are transported to the outskirts of a growing metropolis through the imaginary of photography, the privileged medium of representation for capturing the energy and fluxes of the informal and vacant territories which, according to Solà-Morales, are the correlated spaces to the immaterial conditions of the metropolitan life rather than the stratified tissue of the old urban cities. Curiously, Solà-Morales doesn’t mention the film Terrain Vague, directed by Marcel Carné in 1960, which relates the stories of a group of adolescents that use abandon spaces located at the periphery of Paris to seal pacts related to their marginalised conducts and acts, leading to the suicide of one of the characters. Even if one might associate these vague plots of land to marginalised and obscure activities, the film implicitly builds-up on the situationist ideals of strolling around the city (théorie de la dérive) following its lines of flight (ligne de fuite) to use a Deleuzian terminology. The line of flight is a vector of deterritorialisation which draws an escape from the order, the grid, strata, norms, functions, etc. It’s a witch line that may transform the invisible or the indiscernible into a pure creation or drive to chaos. These informal spaces thus present a paradoxical character that Solà-Morales hasn’t fully grasped, which comes from a different interpretation of the Deleuzian philosophical thought, the part of which still might be operative today, thinking about the examples of ruins (and especially the modern ones), abandon factories and warehouses, deactivated military infrastructures (usually along the coastlines), etc. Due to their difficult condition in the cities’ fabric, usually in problematic neighbourhoods (in the case of old industries) or natural landscapes of difficult access (as in the example of fortresses and other military infrastructures) or due to their large dimensions which make their reuse or reconversion difficult to more domestic or everyday uses, they seem condemned to a marginalised state and decay when it is, at the same time, these very characteristics that give these spaces their unique power and expression which, in turn, should be captured and transformed into something new, following the lines of flight or the creative lines these spaces already contain. One of the most successful examples is the High Line in New York. Shot along different seasons of the year, Joel Sternfeld’s photographs revealed a fantastic landscape created by the winds which remained invisible to most people (with the exception of those whose houses had windows to this elevated and deactivated railway). In these photographs, the former lines of flight become evident. The informal landscape was transformed into a designed garden, nevertheless part of its expression comes from the forces it already contained: the changes through the seasons, the yellows and whites of the Spring, the timid browns between the snow, the ochres and the violets of Autumn, the spontaneous postures of the bushes designed by the winds and the fluid lines of the old railway running through the buildings and sometimes draining into the river, which is not only a sight, but rather an inhabitant of this land. Unfortunately, the transformation of this space brought real estate speculation to the areas that flank the High Line as well, and the old industrial warehouses and factories served by the former railroad became objects of desire for an economy of millions, which corresponds, in fact, to another line of flight, the one that might end in death. Still, the High Line holds within its aesthetic composition a seed of the informal, of the unpredictable, of the chaos (Nature in all its expressions) which transforms both its image and living space. The opposite approach (eradicating all creative forces) would be similar to the one proposed by Steven Holl around 1979 where the structure would be totally re-purposed as a usable space with a row of dwellings along the rail bed housing from the homeless to the upper classes.

Ailanthus Trees, 25th Street, May 2000, Joel Sternfeld. Courtesy of the artist.

In this sense, it is not about the resemblance one might find between the paradoxical state of these spaces with the condition of the metropolis and its inhabitants, between the informal state or condition and the impermanence of the fluxes that draw our present inhabiting condition, but what we believe to be closer to the paradox enunciated by Massimo Cacciari: independently of the immaterial fluxes of information, energy, money, if we are places (in the sense of our most physical dimension), how can we not desire a place? However, this place is not the one of the old city or even of the metropolis, but rather a place that instead of dissolving the contemporary contradictions and paradoxes, uses them to create a place that follows its lines of flight and creates a plane of desire. Deleuze’s concept of space, although Solà-Morales understands it correctly as a plane of forces populated by rhizomatic structures that escape the stratified State apparatus (and with it all the molar institutions, such as family, religion, etc.), shouldn’t be understood as an expression of the immaterial or of impermanence (with its correlated desire for constant movement or dislocation) or even strangeness (which Solà-Morales links to the freudian unheimlich), but in turn exactly of its singularities, its haecceities, its lines of flight or creative lines that allow new metamorphoses and transformations of space itself (the smooth space, as defined by Deleuze, is not the space of virtual reality as many architects understood, but this space populated by singularities - just like the desert - and the proper Deleuzian concept of virtual refers to the real or plane of immanence where intensities circulate just before actualisation or territorilisation, whenever a force is captured into matter-form). Deleuze is not at the opposite side of forms, but understands them as intensive matter, which in fact is a problem that harkens back to the Greeks. As the Portuguese philosopher Maria Filomena Molder reminds us, it was not until Nietszche that it was fully understood what should have been an evidence to the Greeks themselves: “The love of form, as the constitution of a figure sustained by an inner principle of perfection and beauty, is engendered at the heart of a struggle never brought to its end, not against chaos in rigor, but especially as a response to chaos, a projective extension of understanding that surprises the inseparability of the destructive and creative forces of nature, of life.” (3) And “If form dares to nullify the forces of chaos, it is no less evident that the forces, insubmissive, return. Whenever we believe we can annihilate chaos, operating its definitive overcoming, we are stuck with what we might call a dead form, that is, the one petrified in a false configuration, based on the misunderstanding that consists in confusing the force as the enemy of form, since the enemy of form is not force, but its total immobilisation.” (4) Following this idea, Goethe’s metamorphosis implies the awareness of the dangers when form encounters the forces of the chaos, but he finds in it as well an impulse of specification, a force of perseverance which allows something to remain. The work of architecture is a vestige of such combat, resulting from the desire to create a permanence, a presence, which nevertheless still holds, in its expressive identity, a sparkle of what once were the insubmissive forces of chaos - “The creative forces of nature, of life” - returning to us the restlessness of a greater beauty that we are then able to discover in the work of architecture.

In the second excerpt, Solà-Morales rehearses the problem of the contemporary body. However, the body without organs is not the fragmented body of the post-metropolitan and post-capitalist subject. It is not even a body in the sense architects tend to think about, including Solà-Morales. The body without organs is the intensive body, prior to any subject or object. It’s the Dogon egg, as Deleuze and Guattari point out, defined only by intensities, velocities, gradients, kinematic movements that envelop a sensation. It is true that our structures of knowledge are ruined, totally dissolved, whenever a body without organs is formed, because it acts on a molecular scale, beneath the molar entities, in the production of desire (whenever we desire, we construct a body without organs for ourselves). In architecture, we find examples of bodies without organs when a certain work of architecture holds a bloc of sensations, metamorphosing the space into an intensive space defined by intensities, and the living body into an intensive body. The body becomes space and, in its turn, the space becomes body. In certain works of architecture, that compose silence as a spatial sensation, for example, our body is “forced” to remain in silence and to become an attentive listener of space itself, of its inaudible forces that transform light into sound at the same time sound becomes a molecular energy affecting our own proper lived bodies, dissolving the organisation of our organs and making our skin, our stomach, our breathing hear (the fabrication of a body without organs implies first an elimination of all clichés, molar entities, data, everything that may obstruct the free flow of desire, when an undifferentiated organ - the organ is the receptacle of sensation - is formed and starts to circulate in this continuous plane populating it afterwards with temporary organs; in the example given, these would be ears all over through our body - and that’ how the dismantling of the organisation of the organism occurs, Deleuze does not refers to any fragmentation).

Solà-Morales was one of those architects who dare to transpose the Deleuzian thought into architecture, though exposed to the dangers of this translation. Deleuze didn’t like metaphors or comparisons. His examples were literal, as he used to mention. However, for most architects whenever Deleuze spoke of movement, they thought he was referring to the dislocation between two points happening in a space-time interval, and when he was speaking of a body, they thought he was referring to a subject’s body. When he talked about nomads, they thought he was referring to people who live in transit, and not to those who love the Earth as the absolute deterritorialised space. These misunderstandings around the Deleuzian concepts were responsible for an exhaustion provoking a temporary departure of Deleuze from the theory of architecture. Lately, it has been reappearing especially in gender discussions to which the Deleuzian concept of becoming-woman (devenir-femme) may contribute. But once more, the becoming - just like the body without organs (which is also traversed by a series of becomings) - happens on a molecular scale, beyond any preconceived idea or representation of what is a woman or a man. There is also a becoming-woman of the man which has nothing to do with any dress-play of the man or imitating the entity of a woman. Deleuze gives us the example of writing, for instance: “When Virginia Woolf was questioned about a specifically women’s writing, she was appalled at the idea of writing “as a woman.” Rather, writing should produce a becoming-woman as atoms of womanhood capable of crossing and impregnating an entire social field, and of contaminating men, of sweeping them up in that becoming. Very soft particles - but also very hard and obstinate, irreducible, indomitable. The rise of woman in english novel writing has spared no man: even those who pass for the most virile, the most phallocratic, such as Lawrence and Miller, in their turn continually tap into and emit particles that enter the proximity or zone of indiscernibility of women. In writing, they become-women.” (5)

In architecture, the concept of becoming-woman should question the gender connotations and representations in space as the female and male bodies are usually understood as molar entities. Instead, space may engender zones of indiscernibility where the bodies are no longer defined by their forms or sexual organs. For example, instead of understanding Josephine Baker’s house (the project designed by Adolf Loos) as an erotic desire for Josephine’s body, we may think about a becoming-woman and a becoming-imperceptible whenever a body (male or female) swims in the pool lit from above. The bodies, whether female or male, in the water would be transformed into shadows and an undifferentiated sensuality would be given only by their movements and play with light.

Notes

Ignasi de Solà-Morales, “Terrain Vague.” In Davidson, Cynthia (ed.); Anyplace. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1995, pp. 122-123.

Ignasi de Solà-Morales, “Absent Bodies.” In Davidson, Cynthia (ed.); Anybody. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1997, pp. 23-24.

Maria Filomena Molder, As Nuvens e o Vaso Sagrado. Lisboa: Relógio d’Água, 2014, p. 152. Translation by the author.

Idem, Ibidem, pp. 152-153.

Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Capitalism and Schizophrenia: A Thousand Plateaus. New York: Continuum, 2004, p. 304.