The Space of Contemplation: On Glenstone’s Pavilions

The invitation to write for the book about Glenstone’s Pavilions came from the awarded architect Thomas Phifer and the museum’s director Emily Wei Rales. Besides my essay, the book features essays by Paul Goldberger and Michelangelo Sabatino, plus a talk between Adam Greenspan, Paul Goldberger, Thomas Phifer and the Rales, and photographs by Iwan Baan. The book is available here.

Image credits: Glenstone’s Pavilions, Iwan Baan. Courtesy of the artist.

I am sitting in front of a painting at the Museu Colecção Berardo, in Lisbon.

It’s a square canvas painted black, a flat matte black. I cannot perceive any gloss or reflection or any trace of brushwork on its surface. I start to wonder: Is there something more to this Abstract Painting, as it is titled? It’s part of a series of black paintings by Ad Reinhardt, which occupied him in the last years of his life. As I get closer to the painting, trying to decipher its mysteries, the monochromatic black starts to subtly shift. I step back a little, trying to embrace the whole picture again, then move closer one more time, focusing with full attention and opening my eyes wide to permeate them with the greatest amount of light possible. The painting now unveils a geometric division of squares forming a central cross; my eyes begin to notice some reddish, bluish, and greenish nuances within the black around the edges of the forms. These hues appear gradually, as my eyes register the understated changes within the black. In total absorption, a thought arises: when one spends this much time with an object, a person, or a place, looking deep within—allowing it to question us back, even in its muteness—different characteristics, qualities, and details start to emerge, changing one’s very perception. In front of Reinhardt’s painting, this common idea transforms itself into a different question, because the work demands a contemplative gaze (1) to fully engage it: How could the composition of a room lead one’s body to a contemplative state to absorb the aesthetic experience of the work of art? (2)

According to Walter Smith, Reinhardt’s black paintings should be understood in light of his relationship to Eastern art and thought, evoking “the spirit of Vishnudharmottara, an ancient Indian treatise on art and aesthetics” (3) whose “emphasis on the abstract elements of art—its underlying formal structures and rhythms—rather than on subject matter and iconography reveals an important Indian belief about the highest purpose of art. This purpose is not to depict stories or to portray gods and their symbols but to produce a particular state of mind, leading ultimately to spiritual liberation… The purpose of the art object is to produce a particular state of mind. It does not depict or symbolize that state but, by various means, leads the viewer to it.” (4) A museum gallery should, then, by the action of its formal and expressive qualities, lead the viewer to that contemplative state, inducing the body to rest in silence while simultaneously opening its pores—just as I widened my eyes in front of Reinhardt’s Abstract Painting—in order become a fully quiet and attentive body. But this gallery enclosure exists within a vaster system, which in its turn choreographs one’s body through space. It is not only about a one-to-one relationship between one’s body and a painting, but rather between the body and a structure housing numerous artworks. Each artwork appeals to different bodily reactions and thoughts, requiring the design of a seemingly paradoxical space: one that is indifferent to the variety of artworks on display, allowing the body to achieve the desired contemplative state, but simultaneously quite specific in creating a symbiosis between each artwork and the walls that surround it, intensifying the viewer’s experience of each artwork, which possesses a pulsation of its own. Such a museum structure propels changes in the visitor’s bodily reactions (and perhaps even transformations) through the design of its internal architectural rhythms. The space of the museum must express and compose a wholeness from the singularity of its parts.

This idea is also found in the design of Japanese shrines and temples, (5) which are surrounded by nature and composed of several buildings, each one displaying a unique expressiveness and performing a different function. A gate marks the threshold between sacred space and daily common ground, opening onto a large avenue and wandering paths where a visitor can quietly stroll and spend time in meditation and contemplation. Architect Bruno Taut, during his exile in Japan, (6) provides a fleeting impression of such sites: “Beyond the village, amidst a group of lofty trees, stands the main shrine. Mighty cedars encircle it or a combination of ancient cherry-trees, maples and firs. At times such groups rise up out of the plain like unsightly bushes or creep up the mountain side, at others they snuggle close in between the hills with their Shintō gates that are mostly of red painted wood (the main gates being mostly of stone) placed here and there along the avenue leading to the shrine.” (7) Approaching the shrine becomes a rite of passage, a time of preparing the body to silence itself in order to become a receptive surface, replete with thousands of sensory neurons through which sound, movement, light, color, and texture can be felt at maximum intensity. Such sensations are felt without any agitation—instead, they arise like breezes whispering against the skin. These spaces allow a reconnection with one’s body not only spiritually, but also physically.

A similar experience occurs during a traditional Japanese tea ceremony. First, a visitor crosses a beautiful garden with irregular stones placed among the moss; then, hands are rinsed (the same ritual that occurs when entering a shrine, where visitors must rinse also their mouths) over a stone vessel—the tsukubai—with a bamboo scoop before entering the tea house, which is composed of a small room (whose dimensions are defined by the number of tatami mats) with sparse decorative elements on the walls. As Taut describes it: “Here the mind is tranquillized; that is as it should be. All that is exciting, politics, business, ambitions and problems of all kinds, vanishes completely.” (8) During the ceremony, the host holds the bowls for a while without uttering any word or sound, simply observing before placing them on the mat of the adjacent person, who then takes the bowls to contemplate them as well. “This extremely peaceful contemplation of things worked by hand certainly prompts the creation of good things, as only the valuable can stand a quiet look and the silence that follows. The same can be said of the room in which the contemplation takes place,” (9) Taut writes.

The act of walking in nature is extremely important for both experiences as a prelude to the state of contemplation that is, in its turn, shaped and augmented by an enveloping architectural space. One cannot exist without the other—or, at least, it becomes easier to reach that ideal state of mind if the two moments are linked in space and time. How can similar experiences be orchestrated by a museum, allowing each visitor to achieve a complete and faithful experience of the artwork?

***

Amid undulating hills, flowering meadows of indigenous flora, woodlands, shrubs, and open fields in rural Maryland, volumes of various sizes emerge from the landscape, composing a symphony through a scale of heights. (10) On one side, a dense mass of trees embraces the volumes, while on the other, the volumes extend out toward a group of sparse trees, following their rhythm. This view of the Glenstone Pavilions, designed by Thomas Phifer, appears to a visitor’s eyes after an extended walk from the entrance gate (composed of three parking groves near the first volume, the Arrival Hall), marking a threshold between everyday affairs and the art experience to come. The act of walking is, in fact, the first intentional moment, the first design element of the museum—a bodily act where the museum experience begins to unfold. Footsteps, as Michel de Certeau writes, “are myriad, but do not compose a series. They cannot be counted because each unit has a qualitative character: a style of tactile apprehension and kinesthetic appropriation. Their swarming mass is an innumerable collection of singularities. Their intertwined paths give their shape to spaces… They are not localized; it is rather they that spatialize.” (11) As a person walks, their perception of the landscape changes; movement becomes space, an ever-changing experience, as the apparently static and uniform surfaces and masses start to unveil their singularities, their tactile qualities—the many ways the landscape’s components absorb light and throw shadows. I am reminded of Hamish Fulton’s photographs of his walks and how these express a duration of movement, sometimes days—as in A Two Day 59 Mile Road Walk (1976)—or weeks. Fulton says he cannot make any artwork without taking a walk. For him, the walk is the work—“My art form is the short journey”— (12) an experience that cannot be altered, re-created, stolen, or reproduced. The exhibited objects are just evidence of the walk—framed photographs that always include a caption providing information about the journey. If a photograph crystallizes a moment in time, Fulton’s captions give his photographs an expanded sense of space-time, sometimes mentioning animals that he had encountered on his journey or sounds that a still image cannot capture. (13) The act of walking is a container for an aesthetic experience for Fulton, who tries to convey his ambulatory encounters through his photographs and their respective captions. His journey through the landscape—its “tactile apprehension and kinesthetic appropriation”—resonates in the space of the photograph.

Glenstone’s Pavilions. Photograph by Iwan Baan. Courtesy of the artist.

At Glenstone, the visitor is invited to engage with the “art form” of the “short journey,” not only during the walk across the undulating pathway from the Arrival Hall to the Pavilions, but also afterward in his or her movement through the Pavilions’ rooms. It is the act of walking and its carefully orchestrated rhythms that activate and unfold the aesthetic experience of the landscape, the museum, and the artworks. As Fulton says, “Walking is the connecting experience / for a wide range of concerns and disciplines… walking is magic.” (14) These rhythms induce in each visitor’s body correlative states of awareness and contemplation necessary to the art experience. But how does this occur in and through space—through composition, form, scale, interior spaces, and sequences; through materials, light, and all the other elements that participate in the spatial agencement? (15)

Glenstone’s Pavilions. Photography by Iwan Baan. Courtesy of the artist.

At the crest of the hill, the Pavilions’ volumes resemble stones or ancient ruins, extending the ground and framing the sky. Although at first glance they may seem random, their location is extremely precise, aligned according to the cardinal points and following the placement of barns that once stood on the site. Glenstone’s Pavilions follow an implicit lesson taken from anonymous ancient buildings that express, through their relation to topography and their typically simple and clear forms, an intuitive reading of the lines of force of a landscape, endowing the buildings with a sense of permanence—of having been there since the beginning of time. (16) Architect Peter Zumthor gives a similar description of such buildings found in the Alpine landscape: “Well-placed objects never cease to enchant me. I think of buildings that stand in the landscape like sculptures and yet also seem to grow out of it. For example, driving along the Eisack Valley in South Tyrol makes me deliciously happy because I see beautiful self-contained objects everywhere: a monastery, a village, a castle, a little shed on a meadow. I love how sharp and pointed these small and large monuments are. And even when they are gigantic, like fortresses on their cliffs, they do not disturb the landscape, they celebrate it. How they manage to do that seems to be their secret.” (17)

The Pavilions have this same relation to the landscape: they belong to it, enhancing its grandeur, its openness, its subtle variations, its singularities—the compact woodland and the sparse line of trees, the flowing meadows, the native flora. Even the volumes’ material—precast concrete blocks (one foot high, one foot deep, and six feet long)—embodies nature’s own mutability, showing the variation in time, in light, in humidity. If it rains, the concrete becomes darker; when it snows, it becomes shadowless; if the sky is cloudy, it appears to dissolve into the air. The material inherited the very process that gave form to it: the concrete blocks used in the Pavilions are not a commercially available building material, but a custom-made one—the result of two years of casting under various and sometimes severe climatic conditions. Each block is unique, a singularity in its own right; it creates a distinctive, protean whole, which Phifer likens to a tapestry. Phifer’s concrete tapestry brings to my mind the idea of patchwork as Deleuze and Guattari understand it: an example of a smooth space in opposition to a striated space, the latter being the space of the apparatuses of power, the norm, the stratum. Patchwork, they write, “may display equivalents to themes, symmetries, and resonance that approximate it to embroidery. But the fact remains that its space is not at all constituted in the same way: there is no center; its basic motif (‘block’) is composed of a single element; the recurrence of this element frees uniquely rhythmic values distinct from the harmonies of embroidery… The smooth space of patchwork is adequate to demonstrate that ‘smooth’ does not mean homogeneous, quite the contrary: it is an amorphous, nonformal space prefiguring op art.” (18)

The Pavilions’ blocks produce a patchwork of rhythmic values, creating different tones of gray, blue, and silver, radiating light as the sky changes, imprinting movement in the static concrete forms that we typically only recognize in the mutability of nature. The landscape around the blocks changes accordingly as well, creating a mutual dependence. The volumes belong to the landscape just as the landscape belongs to the volumes. This happens, certainly, through the transformation of the material into an expressive matter, when the natural properties of the material are aesthetically manipulated by an artist or an architect. (19) Concrete is already a composite material, formulated from a mixture that can be controlled by selecting, for instance, specific aggregate components. At Glenstone, the custom casting—with its lengthy process and attendant exposure to the natural elements—creates a material able to enhance the effects of weather, light, and other natural elements. This enhancement is not a question of visual perception or the influence of the light or the weather; it’s the concrete itself that changes its composition (as it reacts directly to natural elements), almost like a living matter, like the surrounding flowers and grass and trees.

Glenstone’s Pavilions. Photograph by Iwan Baan. Courtesy of the artist.

Processing slowly through the landscape toward the Pavilions, before the entrance to the first architectural volume, the visitor can pause to admire Michael Heizer’s piece Compression Line (1968/2016). Significantly, it is viewed from above, encouraging a moment of contemplation as the body gently leans down while the effect of a deep cut in the land, whose center resonates, expands, and contracts the landscape around it, is strengthened from this viewpoint. Heizer has two installations on view at Glenstone; his works, especially those built in the Nevada desert, such as Double Negative (1969–1970) and Dissipate, Nine Nevada Depressions #8 (1968), from which Compression Line derives, give form to the surrounding landscape, understood by the artist through its physical properties—volume, mass, and space (terms that belong to sculpture’s traditional nomenclature). (20) But as Colette Garraud points out of Heizer’s Double Negative: “The artist appropriates, in a way, the characteristics of the site, making the immensity and silence of the desert penetrate into the artwork.” (21) A similar effect of penetration and exchange of forces occurs between Heizer’s works and the space of the museum. The topography of the pathway toward the entrance of the museum augments Compression Line’s effects, tying the work and the landscape together through the vertiginous sensations it induces in the viewer. The same intensifying experience occurs when the visitor comes upon Heizer’s Collapse (1967/2016), which is displayed on the top of one of the Pavilions’ volumes, so that the force of gravity is felt keenly. This artwork—an extremely large hollow cubic space within the ground filled with steel beams—doesn’t have any kind of protection around it, encouraging a sense of imbalance, and perhaps even of trepidation, in the viewer.

***

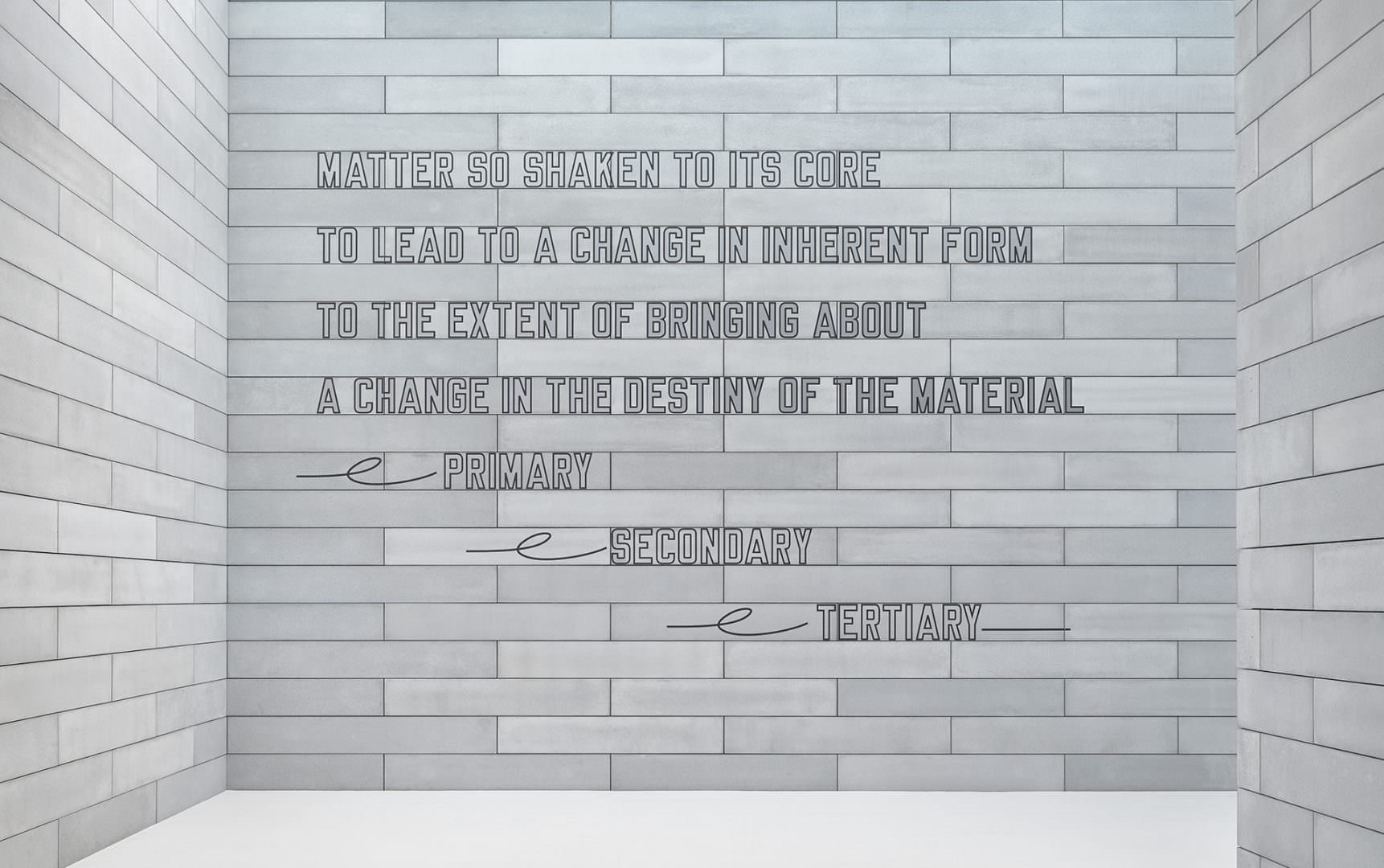

“Matter so shaken to its core to lead to a change in inherent form to the extent of bringing about a change in the destiny of the material. Primary, secondary, tertiary”: At the museum entrance, Lawrence Weiner’s 2002 wall piece confirms the visitor’s experience thus far, and points toward what is to come. This phrase could be applied both to the physical walls of the museum (more specifically, to their material) and to the pieces of art within. In order for a material to become expressive matter, it must reach a limit and exceed it, thus changing its nature. I recall what Louise Bourgeois once said about the process of making The Sail (1988), a beautiful outdoor sculpture, for which she had personally chosen a huge block of the whitest Carrara marble. Bourgeois carved several holes from all sides of the block with extreme care to reach the heart of the stone. She wanted light to emanate from the inside to the outside, so that the viewer would perceive various movements of light on the work’s surfaces not only from light falling from the sky, but also from light radiating out of the various holes in the stone. This could only happen by reaching the center of the stone; in doing so, Bourgeois brought about “a change in the destiny of the material,” finding the very limit of its consistency as a mass.

Lawrence Weiner’s 2002 wall piece. Photograph by Iwan Baan. Courtesy of the artist.

The matter that Weiner’s piece mentions refers not only to physical material but also to all the other realms from which art draws: drives, tensions, dreams, chaos, vague images, unconscious thoughts—all are materials, just as stone, steel, canvas, and paint are. Such matter participates in the work’s aesthetic composition, and is subjected to the same procedures, twists, movements, expansions, contrasts, contractions, saturations, and so forth. In every successful artwork there is always this pursuit of limits, which is what makes a work of art stand on its own. (22) The very rhythm that Weiner imparts to his piece—primary, secondary, tertiary—seems to reflect this pulsation that the artwork inherits from the artist’s leap into the chaos of creation. Significantly, Weiner’s piece is displayed on the entrance wall, with light falling on its surface from high above, acting as a threshold where another rhythm starts to unfold in the space.

Facing Weiner’s wall piece, the visitor is expected to descend down the stairs. Suddenly, around the corner below, light floods the space. The walk through Glenstone’s landscape—the induced and orchestrated alternation between movement and pause—has been preparing the body for this encounter. The body is already enveloped and quieted by the space’s rhythms, but it is not yet fully prepared—the pupils are adapting, blood pressure settling, lungs inhaling. The body now adjusts to this light and the inner world it reveals: a whole living cosmos inside the museum made of water, irises, rushes, and water lilies, which change subtly across the days and seasons through the natural movements of water and wind. It recalls the rock garden of Ryōan-ji (23): this magical and peaceful landscape is framed by the shadows of the passageway that surrounds the Water Court and unites the Pavilions’ rooms underground. Instead of creating a simple frame around the landscape, similar to a landscape painting on a wall (which the visitor can experience in another room), the windows revealing the Water Court bring the tranquility and the silence of the water, the gentle wind patterns on the water’s surface, and the beauty of the flowers into the interior space, producing in the body the desired state of quietness and contemplation. A similar idea is at work in the Brion Cemetery in Treviso, Italy—another lodestar for Phifer—for which Carlos Scarpa designed a garden with freestanding pavilions, linked by semi-open corridors that compress and dilate the space, directing the gaze toward the landscape and to singular moments of ritual. (24) One of these moments is a meditation pavilion—the most intimate space of the cemetery—that stands over a pond full of water lilies, creating a “meditative somberness,” in the “somewhat subterranean world,” as the architectural writer Peter Buchanan writes. (25) The effect is an atmosphere propitious for silence and contemplation; Scarpa experienced such atmospheres during several journeys to Japan. As Buchanan notes, in this work, “instead of Modernism’s abstract and immaterial concerns with concept and space, here is physical mass and sensual matter,” (26) as revealed in the photographs of Guido Guidi, Scarpa’s student, who photographed it repeatedly at different times of the day and in different seasons over a period of almost ten years. Guidi’s photographs—which present a series of the same views through the years—underline the changes that light and shadow create on the rough walls of the building; the spontaneous growth of vegetation climbing and falling from Scarpa’s intricate, geometric motifs; the patterns in the water whenever the wind blows a little harder.

View of the Water Court. Photograph by Iwan Baan. Courtesy of the artist.

At Glenstone, the same effect is at work: light and shadow render time visible in its many manifestations inside the space of the museum. A composed rhythm unfolds again: the light that comes from the Water Court—underscoring the subtle passage of the seasons, the gradations of the flowers’ hues, and the reflections of the water’s surface patterns—plays with the shadows of the massive concrete walls of the galleries. Inside each gallery, daylight (carefully controlled to ensure the artworks don’t receive direct sunlight) falls from above, embodying time and its passage through the day. The rhythm of light to shadow to light not only organizes the space of the galleries, but also induces in the body a correlated rhythm of sensations: from spatial dilation to contemplation to concentration to spatial dilation; “the world that seizes me by closing in around me, the self that opens to the world and opens the world itself,” (27) as Deleuze writes. This correlation between the rhythms of space and the body happens when the thresholds—i.e., within the physical space and within the viewer’s sensitive body—coincide. (28) Along with this rhythm another one appears—that of the artworks themselves, the sensations they create. These sensations are augmented and intensified by the formal qualities of the gallery. Most of the rooms’ proportions and atmospheres were determined in close collaboration with the artists or with the artists’ estates, as the pieces are intended to be on display permanently (or for extended periods). The walls of the room dedicated to On Kawara’s Moon Landing (1969) are close enough to each other for this triptych to be read in continuity, while the light falls from thirty-six feet above into the center of the space, impelling a visitor’s gaze toward the sky’s vastness. The gallery featuring Brice Marden’s Moss Sutra with the Seasons (2010–2015) has a lower ceiling, which emphasizes the sense of horizontality of his nearly forty-foot-long painting; the truncated height also alters the way one moves through the space to observe the five canvases, encouraging close attention to Marden’s calligraphic gestures and to the gradation of colors arranged according to the passage of the seasons, recalling the temperature of a spring or an autumn day. The passage of time is paramount once again, but here it is communicated through the work and activated by a visitor’s steps and thoughts while traversing the room. Rendering time visible is considered by many artists to be one of the most challenging problems in artmaking; in his book about Francis Bacon, Deleuze observes, “To render time sensible in itself is a task common to the painter, the musician, and sometimes the writer. It is a task beyond all measure or cadence.” (29) To render time sensible is also a task for the architect. But how does one build time, understanding it not as a measure but as duration?

Interior view of the Pavilions. Photograph by Iwan Baan. Courtesy of the artist.

In architecture, time is often introduced via natural light, as in the Pavilions’ galleries. Time can also make itself felt through artificial or natural materials that age and change, altering the expression of the building. Some works of architecture require an experience of the passage of time to be fully understood; Scarpa felt this was so for the Brion Cemetery. The effect of time can also be witnessed in the Pavilions, particularly in experiencing the Water Court. And then there are those very rare moments in architecture when time is introduced through the inhabitants’ bodies. This is not a question of perception, but of the postures of the body. Adolf Loos is one architect who obsessively controlled the postures of his buildings’ inhabitants, regulating and precisely defining the variations of intensity in space by controlling the different movements of the body alternated with the body fixed in apparent immobility. In the Pavilions, there are two moments where this occurs, where the body is invited to sit, to rest—where space encourages the body to let time act on it. The first moment is a small platform with a bench over the Water Court, recalling Scarpa’s meditation pavilion at Brion Cemetery, with its delicate wood structure. The second moment occurs as a visitor is walking through the Pavilions and happens upon the reading room: a space with maple paneling, a wall of books, a bench (by Martin Puryear and Michael Hurwitz), and a large opening to the landscape—the living landscape framed. These two moments might be understood as pauses inviting a visitor to take a break from the art experience—a break that might be experienced as a sort of vertigo—but, in fact, they correspond to interruptions in the rhythm, two moments of an even deeper silence, of a greater quietude, which complicates the rhythm of the space. How is time rendered visible through the body? If space is meticulously designed, it can act directly on the body, introducing time. A visitor might not even sit on those benches, or sit for only a few seconds, but time will always be imprinted there: the presence of the body is implied even in its absence.

As a visitor sits in contemplation of the Water Court, looking at the water lilies that have just bloomed and the reflection of the Pavilions playing on the water’s surface, Taut’s words echo: Only the valuable can stand a quiet look and the silence that follows. (30)

Notes

For Reinhardt himself painting was a matter of contemplation. As noted by Walter Smith: “Reinhardt stated in 1955: ‘Painting is… a matter of contemplation for me… Clarity, completeness, quintessence, quiet.’” Smith also quotes David Bourdon, who, in an homage to Reinhardt for Life magazine, wrote that the artist “spends hours in his studio gazing at his works and meditating on still further reaches into the limits of perception and art. Reinhardt's paintings were for him literally objects of contemplation.” Walter Smith, “Ad Reinhardt’s Oriental Aesthetic,” Smithsonian Studies in American Art 4, no. 3–4 (Summer– Autumn, 1990): 38.

This painting of Reinhardt’s was in fact a touchstone for the architect Thomas Phifer during the design process of the Pavilions at Glenstone. During initial design meetings, Thomas Phifer brought several evocative images printed on cards to prompt the discussion with Mitchell and Emily Rales, Glenstone’s founders. Abstract Painting by Ad Reinhardt was the first card shown. Phifer in conversation with the author, March 25, 2020.

Smith, “Ad Reinhardt’s Oriental Aesthetic,” 23.

Smith, “Ad Reinhardt’s Oriental Aesthetic,” 23.

The shrine is usually used for Shintō rituals whereas the temple is used for Buddhist worship. During design discussions with Mitchell and Emily Rales, Thomas Phifer showed various images of Japanese shrines and temples. Phifer in conversation with the author, March 25, 2020.

Bruno Taut was a German architect who felt compelled to leave his home country on the rise of the Nazi party. He lived in Japan between 1933 and 1936, after which he went to Istanbul. During his stay in Japan, Taut wrote several books about Japanese architecture and culture, which popularized the subject among modernist architects (as did Frank Lloyd Wright, who had visited Japan in 1905).

Bruno Taut, Houses and People of Japan (Tokyo: Sanseido Press, 1938), 137.

Taut, Houses and People of Japan, 161.

Taut, Houses and People of Japan, 159.

The landscape project is by PWP Landscape Architecture, led by Adam Greenspan and Peter Walker, who have worked with Glenstone since 2003.

Michel De Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 97.

Colette Garraud, L’idée de nature dans l’art contemporain (Paris: Flammarion, 1994), 127.

Fulton’s artistic records of his walks include not only photographs (always accompanied by a caption/notation), but also paintings, wall paintings, notations, poems (similar to haikus), wall texts/wall poems, booklets, sculptures, etc.

Hamish Fulton, “A Walking Artist,” Mousse, 2019, http://moussemagazine.it/hamish-fulton-walking-artist-galerie-thomas-schulte-berlin-2019/.

Agencement is a Deleuzean concept, usually translated as “assemblage.” However, assemblage might be understood as collage, which is not the case with an agencement, although the latter presupposes a heterogeneous set of elements as well. In an agencement, the elements and the connections between them are able to set up a movement or force. It holds a power within it that is beyond the collection of its parts.

I am reminded of Hilla and Bernd Becher’s photographs of building typologies, compiled under the title of Anonymous Sculpture, which included barns such as these, exhibiting a clear form and a strong relationship with landscape.

Peter Zumthor, “Architecture and Landscape,” in Thinking Architecture (Basel: Birkhäuser Architecture, 2010), p. 100.

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (London and New York: Continuum, 1987), 476–77.

According to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari: “There is only a single plane in the sense that art includes no other plane than that of aesthetic composition: in fact, the technical plane is necessarily covered up or absorbed by the aesthetic plane or composition. It is on this condition that matter becomes expressive: either the compound of sensations is realized in the material, or the material passes into the compound, but always in such a way as to be situated on a specifically aesthetic plane of composition. There are indeed technical problems in art, and science may contribute toward their solution, but they are posed only as a function of aesthetic problems of composition that concern compounds of sensation and the plane to which they and their materials are necessarily linked.” What Is Philosophy? (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 195–96.

Colette Garraud, L’idée de nature dans l'art contemporain (Paris: Flammarion, 1994), 18.

Garraud, L’idée de nature, 18. Translation by the author after the original text: “L’artiste s’approprie ainsi, en quelque sorte, les caractéristiques du site et fait pénétrer dans l’oeuvre l’immensité et le silence du désert.”

“What is preserved—the thing or the work of art—is a bloc of sensations, that is to say, a compound of percepts and affects. Percepts are no longer perceptions; they are independent of a state of those who experience them. Affects are no longer feelings or affections; they go beyond the strength of those who undergo them. Sensations, percepts, and affects are beings whose validity lies in themselves and exceeds any lived. They could be said to exist in the absence of man because man, as he is caught in stone, on the canvas, or by words, is himself a compound of percepts and affects. The work of art is a being of sensation and nothing else: it exists in itself. (…) The artist creates blocs of percepts and affects, but the only law of creation is that the compound must stand up on its own,” Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, What Is Philosophy? (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 164.

The rock garden of Ryōan-ji was a reference for Thomas Phifer in the design of Glenstone’s Pavilions.

The argument that Scarpa designed essentially a garden—one founded on Eastern and Italian traditions—is put forth by Michael A. Stern in “Passages in the Garden: An Iconology of the Brion Tomb,” Landscape Journal 13, no. 1 (Spring 1994): 37–57.

Referring to the green and gold mosaics that create beautiful reflections on the water, Peter Buchanan comments on the atmosphere of the pools of water lilies: “On the soffit of the arch glint green and gold mosaics, giving something of a submarine feeling to this somewhat subterranean world—lending a rich, meditative somberness.” Peter Buchanan, “Garden of Death and Dreams: Brion Cemetery by Carlo Scarpa,” Architectural Review, September 1985, 54.

Peter Buchanan, “Garden of Death,” 54.

Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation (London: Continuum, 2003), 43.

Regarding the “threshold” through a Deleuzean perspective: The spatial threshold at Glenstone is the space between galleries or rooms that overlooks the Water Court. The threshold in a sensation refers to a degree of intensity when the sensation changes its nature (“It is a characteristic of sensation to pass through different levels owing to the action of forces.” Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation, 65).

Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon: The Logic of Sensation (London and New York: Continuum, 2004), 64.

Taut, Houses and People of Japan, 159.