Memory, Image and Time in the Body

“Memory, Image and Time in the Body. On the work of Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela, presented in the exhibition Radial body” is an essay published in the Catalogue of the exhibition Radial body by Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela. This essay expands the ideas unfolded in the exhibition, relating them with the practice of the artists.

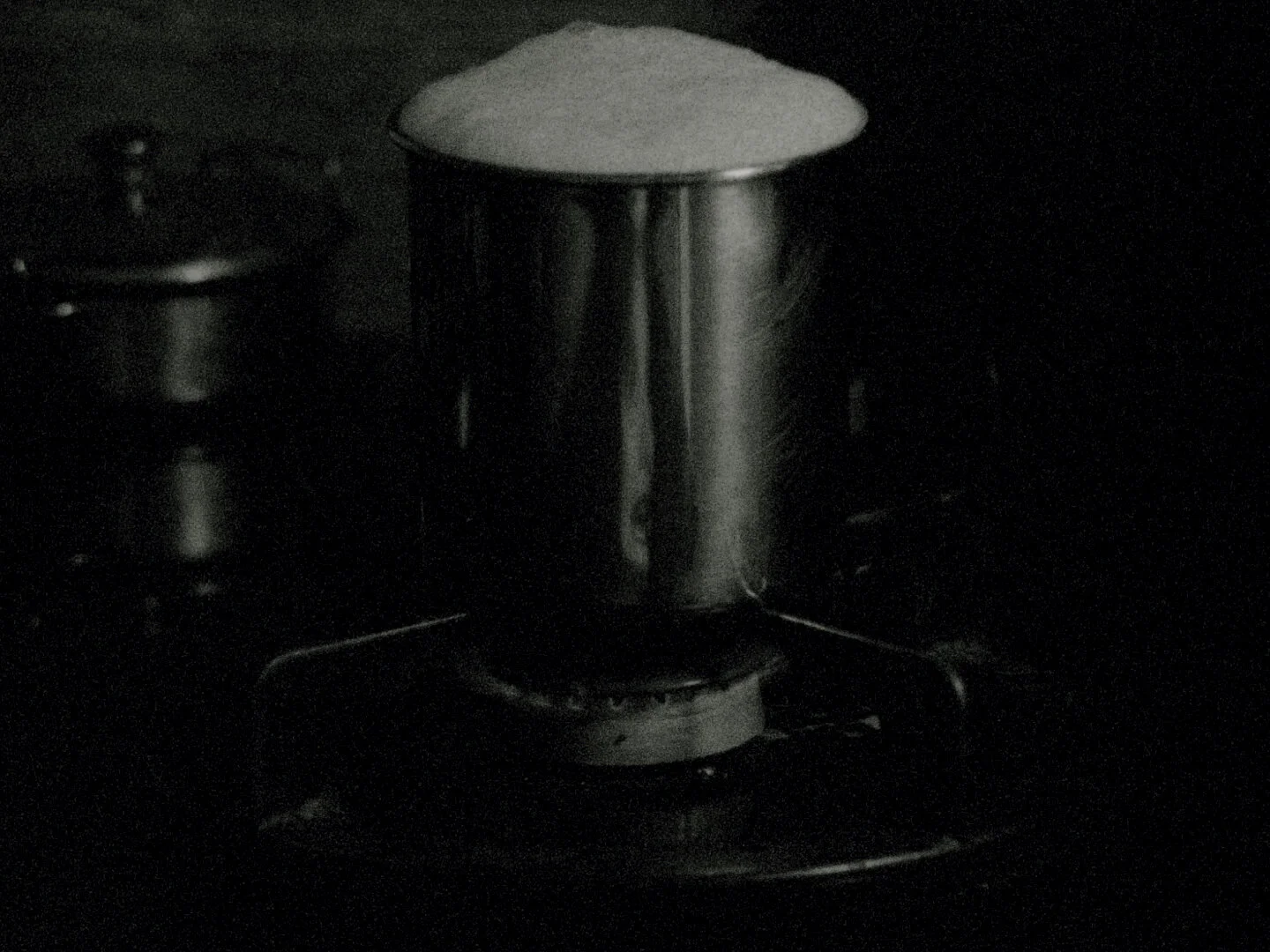

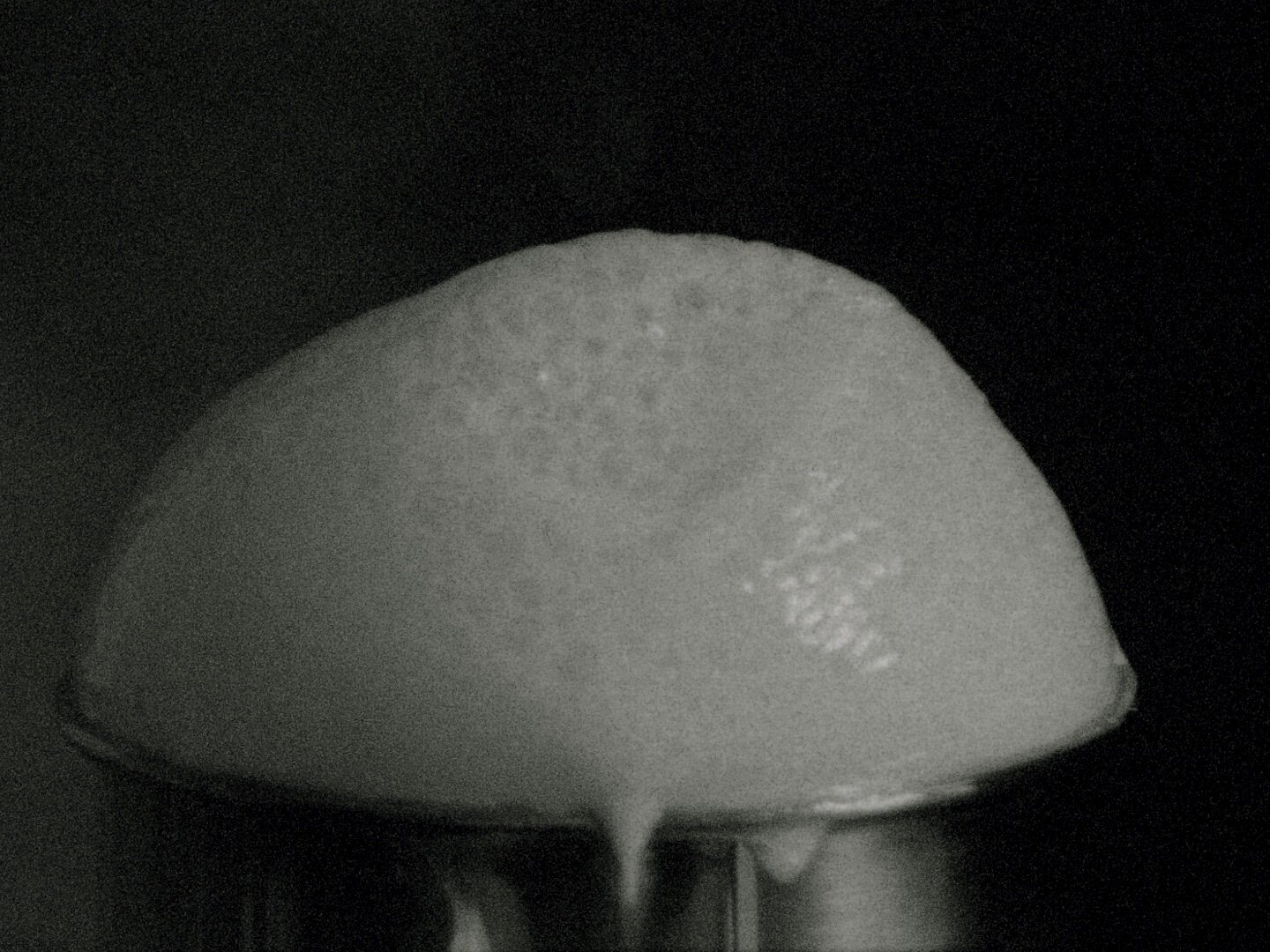

Image credits: Split Milk, Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela, 2019. Courtesy of the artists.

I

Prologue (1)

Memory is the first time-machine that has ever been invented. And the body, before being aware of it, already displayed a primeval memory in its gestures, codified by many millennia. The hand, for example, carries the memory of the pencil, which was once a rock. We don’t need to remember that the hand writes or draws. Even in a state of unconsciousness or in a coma, we witness involuntary remembrances of the body. Nervous twitches, near-instant communications between cells, which may help wake us up. In the drawings, in turn, the memory of the hand appears — the memory of its fast or slow movements, the force it applies on the surface of the support, its weight or lightness, its tactility.

For Barbara Adam and Sandra Kemp, (2) creating a work of art (3) is like a portal in time, in the sense that it expresses a desire to escape from the present and because of what it symbolises and determines in the bodies — their inescapable mortality. As such, a work of art can be understood as something that freely passes through time — from the past in which it was conceived (after it comes into being, the work immediately belongs to the past); to the present that observes it and holds it in its inquisitive gaze; to the future which this gaze inevitably launches it towards. A future in which the work of art will bring about new thoughts — because, from it, other, new images will be created.

“New modes of thought and expression are made possible through the visual. Importantly, the creation of artefacts opens up the realm beyond the present and allows for the free movement in time, given that the creation and representation of the inescapably impermanent world in permanent form facilitates time-binding and time-dis- tanciation practices that far exceed the capacity of spoken symbolic language. As such, the creation of artefacts can be seen as enabling, as opening up what is possible and what can and could be. Seen through a temporal lens, artefacts become agents of future, temporal extensions of their makers, holders and users.” (4)

In this sense, we can think of the work of art as appealing to a memory which is as much about the past (being an extension of its creators) as it is, at the same time, virtual — specifically when, in future encounters with the Other, it interferes with the Other’s memories, with other pasts, which reshape it. It will therefore retain in itself a remnant of pure time, which allows for this free movement of time that the authors refer to. This time, which the work of art preserves in it, doesn’t correspond to the time that the work of art can be an expression of (considering that a work of art is, in part, determined by its context of production); rather, it resembles Gilles Deleuze’s crystal-image, conceived from Henri Bergson's theory of memory.

In Matière et Mémoire (Matter and Memory), Henri Bergson begins by describing two forms of memory, separating them first in order to describe them, as they don’t exist in isolation; on the contrary, they mix and merge in a very intimate way. The first form concerns the perception that triggers movement or action, in which our sensory-motor scheme is continuously precipitated, as with the repetition of gestures in the acquisition of a motor habit or the learning of a colour lesson, in which the repetition of reading engenders its memorisation. (5) “Always bent upon action, seated in the present and looking only to the future.” (6) The second one records, in the form of memory-images, all the unrepeatable events of a person’s life and respective details. According to Bergson, this memory allows for the intellectual recognition of a previously experienced perception, in which we can take refuge whenever we want to access the image of our past. (7) He also adds, summarizing: “The past appears indeed to be stored up (...) under two extreme forms: on the one hand, motor mechanisms which make use of it; on the other, personal memory-images which picture all past events with their outline, their colour and their place in time. Of these two memories the first follows the direction of nature; the second, left to itself, would rather go the contrary way. The first, conquered by effort, remains dependent upon our will; the second, entirely spontaneous, is as capricious in reproducing as it is faithful in preserving.” (8)

Memory-images (which carry with them the individual trace of subjectivity) are continually updating themselves in the perception of the present. This happens when we look for similarities, traces or details of the reality before us, in order to better understand (if memory didn’t intervene, our perception would be pure: through it, everything would be understood as new, as a perpetual present). As Bergson explains, the past is constantly updating itself in the present, meddling in action, making movement a reality. In his famous inverted cone diagram, the circular base of the cone is set on the past, and its summit — the unceasingly advancing present — moves along the plane it touches, whose intersection corresponds to each person’s actual representation of the universe. The summit concentrates the image of the body - that privileged image among all the images that make up the material world - which receives and returns the actions that emanate both from the images that make up the mobile plane of experience (where the summit moves), and those that come from the horizontal sections of the memory cone, from the past to the present, from the virtual to the actual. “The bodily memory, made up of the sum of the sensori-motor systems organized by habit, is then a quasi-instantaneous memory to which the true memory of the past serves as base. Since they are not two separate things, since the first is only, as we have said, the pointed end, ever moving, inserted by the second in the shifting plane of experience, it is natural that the two functions should lend each other a mutual support. So, on the one hand, the memory of the past offers to the sensori-motor mechanisms all the recollections capable of guiding them in their task and of giving to the motor reaction the direction suggested by the lessons of experience. It is in just this that the associations of contiguity and likeness consist. But, on the other hand, the sensori-motor apparatus furnish to ineffective, that is unconscious, memories, and the means of taking on a body, of materializing themselves, in short of becoming present. For, that a recollection should reappear in consciousness, it is necessary that it should descend from the heights of pure memory down to the precise point where action is taking place. In other words, it is from the present that comes the appeal to which memory responds, and it is from the sensori-motor elements of present action that a memory borrows the warmth which gives it life.” (9)

Most of the past remains virtual, however. It is never updated, because it doesn’t find in the present the necessities required by the intentions of the sensori-motor mechanisms. “But, if almost the whole of our past is hidden from us because it is inhibited by the necessities of present action, it will find strength to cross the threshold of consciousness in all cases where we renounce the interests of effective action to replace ourselves, so to speak, in the life of dreams.” (10)

Each moment of our present corresponds to a split in two directions: one of them turned to the future, to action, making memory-images come down from the various sections of the cone to be actualised in a new, fleeting present; while the other, the one that won’t be actualised, will remain as pure memory, as Bergson calls it, and remain virtual. It is essentially from this idea of Bergson that Deleuze defines the crystal-image: “What constitutes the crystal-image is the most fundamental operation of time: since the past is constituted not after the present that it was but at the same time, time has to split itself in two at each moment as present and past, which differ from each other in nature, or, what amounts to the same thing, it has to split the present in two heterogeneous directions, one of which is launched towards the future while the other falls into the past. (...) Time consists of this split, and it is this, it is time that we see in the crystal. The crystal-image is not time, but we see time in the crystal. We see in the crystal the perpetual foundation of time, non-chronological time, Cronos and not Chronos. This is the powerful, non-organic Life, which grips the world. The visionary, the seer, is the one who sees in the crystal, and what he sees is the gushing of time as dividing in two, as splitting. Except, Bergson adds, this splitting never goes right to the end. In fact the crystal constantly exchanges the two distinct images which constitute it, the actual image of the present which passes and the virtual image of the past which is preserved: distinct and yet indiscernible, and all the more indiscernible because distinct, because we do not know which is one and which is the other. This is unequal exchange, or the point of indiscernibility, the mutual image”. (11)

The crystal image has two definite sides, which establish the smallest circuit between them, in which each face assumes the role of the other, indiscernibly. “In fact, there is no virtual which does not become actual in relation to the actual, the latter becoming virtual through the same relation: it is a place and its obverse, which are totally reversible. These are 'mutual images' as Bachelard puts it, where an exchange is carried out. The indiscernibility of the real and the imaginary, or of the present and the past, of the actual and the virtual, is definitely not produced in the head or the mind, it is the objective characteristic of certain existing images which are by nature double.” (12) This smaller circuit of coalescence no longer represents time, not even its non-linearity or the independent oscillations of the succession of events (as it happens with some time-images deriving from movement); it constitutes time itself, the time we inhabit and which we move in. Memory, which leads from our dreams to our actions, coats time itself. “Bergsonism has often been reduced to the following idea: duration is subjective, and constitutes our internal life. And it is true that Bergson had to express himself in this way, at least at the outset. But, increasingly, he came to say something quite different: the only subjectivity is time, non-chronological time grasped in its foundation, and it is we who are internal to time, not the other way round. That we are in time looks like a commonplace, yet it is the highest paradox. Time is not the interior in us, but just the opposite, the interiority in which we are, in which we move, live and change.” (13) Without memory, there is no time. Memory not only makes time tangible, it makes us beings of time.

It is true that Deleuze conceptualised the crystal image from certain cinematographic images, in which the simultaneous divisions, exchange and indiscernibleness between past and present become easily visible, using cinema’s own tools. The very duration of the image undergoes a mutation, opening up (or multiplying through mirrors placed face to face or other film devices, as in several examples mentioned by Deleuze) to take time as its only expression. It is then that we begin to inhabit the image, inhabiting time, within time, that time which never ceases to divide itself into two, which makes the present pass and the past be preserved, which holds us and expands us, simultaneously and continuously.

Returning to Barbara Adam and Sandra Kemp's essay, and curiously enough, the authors refer to a kind of eternal return that exists in the repetition and renewal of patterns and rhythms throughout our lives (such as the rhythms of growth, aging, healing, regeneration and reproduction), which we can come to understand as the present always passing, actualising itself in certain forms. This renewal, they add, does not refer to a change in time, but in itself it constitutes time, endowing “beings with memory, foresight, and the capacity for synthesis”. (14) However, this constant renewal of patterns and rhythms can only exist if the past is preserved exactly as virtual, never actualised (a past never lived, as Bergson would say). In seeking to understand the relationship that arises from this temporal dilation (correlated with constant renewal, which is nothing more than the constant division between actual and virtual time) when thinking about forms and objects, especially artistic objects, the authors also note how a broader temporal framework reveals connections that would otherwise remain invisible — namely, what connects us to the primary matter of which we are all composed, what connects us to the universe (the past that is preserved in itself). (15) (16)

To paraphrase Deleuze, the work of art is not time, but it allows us to see time, and places us face to face with pure memory. Part of an artworks mystery consists in revealing that part of the memory situated in its own depth, — an impersonal memory, which often takes on the name of dream or magic. Relevantly, the actual image, which the work of art constitutes, is always an image of a past that was only present at the moment of conception which then unfolded, extracting from the present a virtuality or pure memory that will be preserved in the work and which therefore allows for free movement in time. Similarly, only a part of the work will be able to actualise our own memories, while another part will always remain pure in the past. But which works are these, that show us how we are interior to time “which divides itself in two, which loses itself and discovers itself in itself, which makes the present pass and the past be preserved?”. (17)

Though saving the classification of crystal-image for cinematographic images (of which Leite Transbordante (Spilt milk), will be the ultimate expression), Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela’s different works in Radial body have this power to allow us to see how we inhabit time — a time in which present and past, real and imaginary, body and universe become indiscernible, in which perception and memory coincide.

II

Gouache drawings

During preparatory work for the Radial body exhibition, the artists created a vast set of small gouache drawings, of which a small selection was presented in the exhibition and a larger selection is included in this publication. Their suggestive titles both evoke and place us before these virtual images of a pure past, that has never been lived, and which will remain as virtuality in the work of art. At the same time, it is as if we ourselves were split in two, living within time: contemplating, on the one hand, the present that passes by, the work before our eyes, recognising in it our memories; and, on the other hand, admiring the past as a whole, which in reality is all that circumscribes us and is present in us — not as form, specification or actualisation, but as time in its pure state, the time of coalescence that connects us to the composition of the universe, to stardust. Extraordinarily, they exist in the work as latent forces and not as representations (or even sensations), being given to us through the geometric compositions, through the abstraction and synthesis they perform by retaining the free, organic movement that precedes them. The drawings configure both what we can recognise of ourselves in them and what lies outside of us. In Alvor (First light), for example, we can see the sun rising, repeatedly, by the continuous rotation of the Earth. Or we can see ourselves waking up or dreaming, separating ourselves from matter and rising to the sky, or we can simply observe the light in its spectral composition and, with it, the dawn of life. The rhythm, the movement suggested by its fan-shape, the resulting apparent symmetry and the bright colours reveal to us, as if in a perpetual and invisible circle, these two coexisting dimensions of time, from a pure past (conserved in latent force) to the past which always creates a new present.

Disco celeste (Sky disk), produces an enigmatic Alvor-like effect. It once again depicts a continuous movement, re-made in two opposite directions, mirrors of each other, from inside to outside, in perpetuity. The bright colour emphasises the intersection of the two infinite movements, but the force (of the movement, attracting our gaze) is found in two centres that seem to revolve around each other. Regardless of any explanation, these forces are retained in the drawing and can be reactivated, actualised in the body at any moment, paradoxically maintaining its virtuality. The title of the drawing evokes the Nebra sky disk from the Iron Age, (18) which is speculated to be the oldest representation of the celestial dome. Its point-covered surface would represent the stars — it is possible to make out the Pleiades constellation —, and a large circle and crescent would represent, respectively, the sun and the moon. The disk is also believed to have been used as a complex astronomical clock for synchronising solar and lunar calendars, when properly aligned. Archaeological objects are often interpreted as time capsules, allowing us to unveil rituals, habits and ways of life that are specific to certain periods and communities. The Nebra sky disk, in particular, goes beyond a representation of its original time, of its contemporary present. It creates a heterogeneous time in which past and present coexist, as demonstrated by the simultaneous existence of two systems of temporal measurement, dependent not on the sequence of events (as in chronological time), but on the singularity of astronomical events which, in turn, is inseparable from the time that they preserve in themselves.

Alvor’s motif turns up again in Radial. This time it accentuates the double movement of contraction and expansion, of closing and dilation, which is never reduced to a single direction. It is usual to come across this repetition of motifs inherent to the geometric language of the artists and which, in their constant renewal, drawing after drawing — or rather, between drawings —, achieve that infinite movement of a continuous spiral, or of a time that necessarily exceeds that of perception. Colours repeat themselves, often creating mirror rhythms of black both in the internal composition of the drawing and in the sequence between drawings. This sequence, however, is not predefined. Although they may belong to a single series (created by the repetition of certain patterns, colours, movements, rhythms, apparent symmetry, etc.), the drawings do not have a predefined sequence, and can be arranged freely. In each dialogue, however, there is always this relationship (which precedes them, too, and which is retained) between form and time, between perception and memory, between present and past, a mirror of our own condition in the universe as body-memory, body-nature and body-cosmos. Since there is no predefined order, our relationship with what is apparently external to us is not predetermined either. On the contrary: the movement that passes through the drawings and captures us in its centre (much like Vitruvian Geometry), makes our relationship with nature, the cosmos, and the divine just as free and indiscernible — as we see in Vénus, Extraterrestre, Espantos and Estrela (Venus, Extraterrestrial, Wonderments, and Star). This indiscernibleness is extremely important for us to understand how we are not only interior to time, but also to nature and the cosmos, a fact which each successive drawing reveals to us (hence the frequently strange and seductive character of Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela’s work, wonderfully confirmed in the recent film A Dança do Cipreste (The Cypress’s Dance)).

Pino Invertido (Headstand), Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela, 2020. Courtesy of the artists.

The relationship between geometric form and time has been present in the artists' work since their first collaboration. By way of example, Gradações de Tempo sobre um Plano (Gradations of time over a plane), from 2010 – still on-going, the artists' first project as a duo, is made up of non-sequential film chapters, in which each chapter is initially described by a composition of geometric figures. Naturally, the film isn’t reduced to this sort of visual index. The geometric figure and, above all, the infinite possibility it contains through fairly simple operations such as repetition, association, multiplication, among others, as well as the simultaneous operations of abstraction and synthesis that are inherent to it, presuppose some sort of primary recognition. The geometric figure is immutable and perpetual. Even when it is given a meaning, that meaning is always external to it, derived from an order other than the internal laws of its visual composition (how many meanings have been ascribed to the circle, for example?). It can also function as a hidden language of nature (as we see in A Trama e o Círculo (The Mesh and the Circle), 2014, or in O Livro da Sede (The Book of Thirst), 2015–2020, as part of its eternal return, in their cycles of constant renewal, which, as stated earlier, find their pure germinating force in the past.

III

Memory Room

In ancient Greece, it became common among the most gifted speakers to practice the Art of Memory — also known as "mnemotechnics" —, considered a technique of Rhetoric. It allowed a speaker to deliver his speech by heart, word by word, using a technique of mental association between places and images (loci and imagines). About the imaginative processes of this technique, Bergson curiously says: “The object of this science (mnemotechnics) is to bring into the foreground the spontaneous memory which was hidden, and to place it, as an active memory, at our service; to this end every attempt at motor memory is, to begin with, suppressed. The faculty of mental photography, says one author, belongs rather to subconsciousness than to consciousness; it answers with difficulty to the summons of the will. In order to exercise it, we should accustom ourselves to retaining, for instance, several arrangements of points at once, without even thinking of counting them: we must imitate in some sort the instantaneity of this memory in order to attain to its mastery. Even so it remains capricious in its manifestations; and as the recollections which it brings us are akin to dreams, its more regular intrusion into the life of the mind may seriously disturb intellectual equilibrium.” (19)

In the classical tradition, the Art of Memory consisted of imagining a building, or recreating an existing building mentally, following certain principles to facilitate the distribution of images throughout the various spaces of said building and their respective memorisation. Frances Yates, (20) a historian of this art, mentions that the different spaces of the building should be large, well proportioned and well lit, according to a rhythmic and precise sequence. The author also reveals that, similarly, there were principles for how to select the images associated with each of the spaces in the building, because not all images have the immediate power to stir mind and memory. The speaker should therefore favour unusual, dramatic, grotesque, sublime, obscene or comic images. (21)

Mnemonic images come from the depths of memory. They hardly play a role in immediate perception, since they are not (and probably never were) images generated by the sensori-motor system. On the contrary, we dare say that it is the virtuality they possess that allows us to freely exercise thought (and its inherent violence), so much so that they are images that are never actualised except in another image that does not correspond to them, an image resulting from the association place-image — this one actualised, but in speech. They will always be images that motor memory does not actualise. Thus, they shall always retain a virtual, hidden side.

It was probably this power of mnemotechnics what motivated Giulio Camillo Delminio (1480-1544) and Robert Fludd (1574-1637) to think and design models for "Memory Theatres." Camillo, based his design model for "Memory Theatres" on the Roman theatre theorised by Vitruvius, while Fludd based his model on the Globe Theatre (associated with William Shakespeare’s plays during the reign of Elizabeth I). Camillo and Fludd argued that their theatres had a magical quality, since they corresponded to a real materialisation of human memory, wherein could fit all the things that the mind can conceive, including the virtual ones lying in its depths. Whoever entered these theatres could access the totality of the knowledge of the world (the pure past, we may add) and its complex connections, including the hidden connections that unite man with the celestial universe and the divine (or supercelestial world). The centre of these spaces was occupied by man (the Vitruvian man occupying the centre of the circle, the most perfect form of nature that men of the Renaissance believed to be an expression of the divine), while the space around him was organised according to the many constellations of the zodiac and filled with images, often with obscure meanings, some of which pertaining to cabalistic teachings and myths. The same image could trigger very different meanings associated with other images. Thus the image would traverse the thousand and one wondrous labyrinths of the mind, including dreams, fantasies, and the most terrible of fears.

Inspired by Camillo and Fludd’s "Memory Theatres," Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela created the work Sala da memória (Memory Room) in 2015. (22) This work took the form of a fujitrans print, a translucent silver halide colour print material suitable for backlit exhibitions like the light box that gives the drawing its enigmatic depth. This depth is accentuated by the symmetrical composition of three planes — each distinct in colour — in which a door appears, placed equally symmetrically in relation to the plane. The abstract space seems to represent, simultaneously and paradoxically, a labyrinth or a place to which we can escape and remain there as long as we like, or, if we evoke the original meaning of the memory theatres, unveil some (hidden) reality through the order underlying its composition. This order, however, will always emerge from the desire of those who remain long enough in the drawing, those who seek to access the pure memories in the depths of their memory.

Sala da memória (Memory Room), Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela, 2015. Courtesy of the artists.

The artists later produced a serigraphic version of the Memory Room. For the exhibition Radial body, the drawing finally acquired the three-dimensionality already hinted at in the light box. Like the models of the memory theatres of Camillo and Fludd, the Memory Room for Radial body, 2020, converted this virtual background into a habitable space, whose proportions resonate with the body that is seduced to remain inside it. A minimal silver fir structure supports twelve sliding doors, inspired by shoji panels, (23) with an extremely delicate frame and translucent silk panels dyed by hand in different colours, one colour per plane. On the central door of eachof the four sides, we unfailingly recognise the door from the original design, painted red.

Flanked by the red walls of Galeria da Boavista that hosted the exhibition Radial body, the structure acquires an ineffable lightness, a magical luminescence, resembling crystal. On one side, with the light coming from behind, its surfaces become more opaque, the planes of colour more defined between the wooden frame. On the other side, backlit, it lights up in splendour from the inside, shining a thousand shades of scintillating red — which, depending on the passage of the day, fluctuate between radiant and lively or solemn and calm. Almost as if to confirm Goethe's words about the colour red: when deep and dark, it conveys an impression of gravity and dignity; when light and clear, it metamorphoses into grace and attractiveness. (24) The chromatic intensity (in the Radial body exhibition, this intensity is further reinforced by the application of red filters on the outside windows of the gallery) creates an atmosphere of a dense and voluptuous veil around the structure. At times it makes it seem as if it was levitating, bright and suspended of its own volition, enticing the body to remain inside a kind of trance or dream and to see itself from inside out, from its innermost dimension: its memories.

Sala da Memória para Corpo radial (Memory Room for Radial body) as displayed on the exhibition. Photograph: André Cepeda.

The different degrees of transparency-opacity convert the bodies — the ones inhabiting the interior of the structure, and those that move outside, and vice-versa

— into shadows or native movement-images, more or less fleeting, more or less clear — as in the traditional Japanese house, where the use of shoji panels allows the creation of an intimate space inside the house, unveiling reality and the outside world according to a desired degree of translucency. An intimate space is not a private or interior space, although it can be contained within one. It is a space in which the body can be one, whole, and fly over itself, through its interior dimension, as practiced by various meditation techniques in Oriental cultures.

IV

Image-movement, image-time

The work of Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela is usually associated with moving image and film. In spite of this, their work almost always appears in connection with other artistic expressions, including inhabited sculpture. That is the case with Animal Vegetal Mineral (Animal Vegetal Mineral), 2018, for example, in which a sculpture evokes a “temple of dream and darkness” (25) whose inner cavity has to be penetrated in order to discover the wonderful dream world of “introspective landscapes and night travels,” revealed through six film projections. (26) Habitantes de Habitantes (Inhabitants of Inhabitants), 2016, is a structure that resembles a totem or a house duplicated by mirroring itself, housing several abstract paintings. This structure is equally inseparable from the languid atmosphere of the installation surrounding it, made up of films, paintings and flat sculptures that occupy the floor (its verticality, in fact, creates an unstable balance when almost all the other elements are spread out on the floor, like cats pleasantly stretching in the sun...). In Memory Room for Radial body, the interior remains empty but only apparently so. It calls for a presence of the body as the body’s proportions resonate in this space (thereby alluding to one of the rules defined by Romberch in his treatise on artificial memory which states that, in order to contain a mnemonic image, a mnemonic place should correspond to a Vitruvian-like human figure with its arms outstretched). (27) It calls for a presence of the body through the encounters that give rise to the body and itself, its memories, among other bodies and other works. It also calls for a presence of the body because the depth it reaches when, from within, it establishes different visual relations with other works on display (namely, movement-images of other bodies and other memories).

The movement-image appears, in fact, almost always as a component of an installation — though it is nevertheless undeniably imbued with autonomy, singularity and expression, the result of the artists’ exploration using cinematographic means, forms, and thought. Despite its undoubtedly experimental character, some specific features do stand out. We oftentimes sense a certain tactility and manual dexterity in the image, as in the continuous and subtle movement of flowers, leafs and bones creating an “atemporal flow” in the six-channel installation in Meia-Noite (Midnight), 2019. (28) This never-ending flow is the result of a manual process of assembly and underwater filming that lends the image and the movement an ineffable sensuality, as the image creates a sensation in the body for which it shows no trace, trapping us in that atemporal flow, or rather, in a continuous and infinite time, which no longer depends on movement. Paradoxically, because the images are in perpetual movement, they create a time extemporaneous to movement.

Time, rather than movement, is what reveals the image. The film doesn’t tell a story, nor does it follow a narrative. Rather, it results from a collection of fragmentary, heterogeneous images, in which each image describes the World, its world, that of its composition, and the external World, because they are almost always images that go beyond Being, that come from dreams or nightmares, from an (almost) unbearable visual crudeness and truth. “There are few things we want to say that images don’t say themselves, that a film can be a maze that revolves around itself, in which we get lost and find ourselves,” write, film, and read the artists in A Trama e o Círculo (The Mesh and the Circle), 2014. Each image contains a world, it tells itself, both for itself and for those who dare gaze upon it. These images sometimes hurt, too. They touch us in the places we would least suspect, because this visual rawness is sometimes a mirror of another rawness that exists both in the human depth as well as in Nature. But there are also primary instincts that awaken sensations of pleasure. Experimentation with film is part of a double and paradoxical effort. On the one hand, it removes the superfluous, the cliché, the veils; it penetrates, it digs into and reveals in the image what in man is purest and most distant in time, bringing him closer to Nature (even the similarities created between abstract geometry and natural forms, in many films, show this indiscernible zone between man — understood as a cultural being, too — and Nature). On the other hand, it feeds the dream, the daydreams, the catharses coming from another space, from the imagination — notwithstanding the fact that artists create images where the real and the imaginary often merge and revolve around each other.

We can find some of these ideas in the film O Livro da Sede (The Book of Thirst), 2015–2020, presented in the exhibition Radial body. Time does not derive from movement; on the contrary, it is the time that the artists assign to each image that determines movement. This movement is that of the camera (there are no moving characters, no action), a thinking camera that looks for similarities, resonances, disparities in the images, that is boosting thought, for example, provoking and questioning the relationship that exists between sexuality, animal and man. The film is composed of a collection of photographs by the artists, which bring together memories of get-togethers with friends and some of their personal interests (which we find throughout their work). Presented on a loop and with a mind-boggling shrill sound these images are sublime and suffocating in their beauty, as well as strange, violent and disturbing. In spite of their autobiographical nature, the images show the infinite oscillations of the experiences of the Being, a variety which creates a space of empathy and sharing across various states of mind. These range from delight, drunkenness, astonishment and terror to a deep sleep (or dream) to banal experiences and trivial gestures or extravagant manifestations. We may witness these sensations in the masked bodies, in the dance of light movements (which only photography captures), and in what belongs to the depth of the human mind which passes through the indiscernibleness between man and animal, or through the empathy that suffering creates in us and from which we cannot look away, evocative as it is of our own end.

V

Crystal-image

Leite Transbordante (Spilt Milk), 2019, is an extremely dark film, lighting-wise, that needs to be watched in an even darker room. When we first saw it, the image of a short story by Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, called Silêncio (Silence), clearly came to our minds. It was evening, and a woman paced to and fro in her house, performing small household chores, breathing in the silence and tranquillity. There was perfect unity between the woman, her home, and the Cosmos. “(...) The night stars outside revolved slowly around this silence, and their imperceptible movement took on the order and silence of the house. With her hands touching the white wall, Joana breathed, softly. There was her kingdom, there in the peace of nightly contemplation. From the order and silence of the universe rose an infinite freedom.

She breathed that freedom which was the law of her life, the nurture of her being.” (29)

The silence was an expression of this peaceful union, until the moment it was broken by another woman's piercing scream, followed by a pause. Time and space are suspended. And other cries followed. “A naked, stray, lonely voice. A voice, which grew deformed, from scream to scream, distorted until it had become a howl. A howl, hoarse and wild. Then the voice weakened, quietened, took on a sobbing rhythm, a wailing tone. But it soon grew again, with fury, anger, despair, violence. In the peace of the night, from top to bottom, the screams rent open a great rift, a wound. Just as water pours into the dry interior when a breach is opened in the hull of a ship, so too, through the crack that the screams had opened, terror, disorder, division, panic now penetrated the interior of the house, of the world, of the night. (30) It was this woman’s face that appeared to us in the milk boiler: a disfigured face that screams but can’t be heard, which extends endlessly and slowly throughout the film until the very last moment, in which it becomes definitely locked in place. The woman's immobility, her astoundment, takes place in a time that is alien to the one in which the milk boils, It is impassive and takes on the shapes that the air and fire carve out of it, focusing our attention to its spontaneous beauty. The two times engender a suspended time or a continuous present in which past and present (and future, this being the present that follows) juxtapose and shuffle the alternation of images. This time is sited between the temporality of the boiling milk and the woman’s mute cry, between beauty and horror, between daily life and that which goes beyond it, and is thus opening a rift in the universe. Time, its passage, and the duration it is given, is a recurrent theme for Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela. In this film, it is almost annulled, both because of the simultaneity of disparate times and because of the limit the artists impose on the movement of images.

“An echo of sobs and footsteps hung for some time in the heavy air of the street. Then the silence returned. An opaque and sinister silence, in which one could hear the dogs rooting about. Joana returned to the room. Everything now, from the star’s fire to the table’s polished shine, had become foreign to her. Everything had come about an abrupt accident, disconnected, orderless. Things were not hers, they were not her, nor were they with her. Everything had become alien, everything had become an unrecognisable ruin. And, touching them without feeling the glass, the wood, the whitewash on the walls, Joana crossed her house like a stranger.” (31) Throughout the film, we hear what seem to be footsteps, steps that sound like beats or beats that sound like footsteps and, like Joana, we pass through the film like foreigners, suspended in the image and stuck in time, while our continuous present moves forward in a loop.

The artists created the smallest circuit, as Deleuze would put it, between the actual image and their virtual one, in which present and past converge (with sound contributing to this coalescence as well), and the real and imaginary become indiscernible, making Leite Transbordante a perfect example of a crystal image. “What we see in the crystal is time itself, the gushing forth of time. Subjectivity is never ours, it is time, that is, the soul or the spirit, the virtual. The actual is always objective, but the virtual is subjective: it was initially the affect, that which we experience in time; then time itself, pure virtuality which divides itself in two as effector and affected, «the affection of self by self» as definition of time.” (32) The “affection of self by self” or that woman’s perplexity which is, in fact, our own.

Stills from Leite Transbordante (Spilt Milk), 2019. Courtesy of the artists.

Notes

In this title, Body takes on a double meaning: it refers both to the human body (and its inherent complexity) and the body of work of the artists Mariana Caló and Francisco Queimadela, in which we permanently and irrefutably come across these themes (memory, image, and time).

During preparatory work for the Radial body exhibition, the artists shared different references, from visuals to bibliographies, including the essay "Time Matters: faces, externalized knowledge and transcendence,” 2019, by Barbara Adam and Sandra Kemp.

The authors refer to "artefacts," but the examples they give throughout the text clearly concern artistic objects, although in some cases they could have ritualistic functions.

ADAM, Barbara and KEMP, Sandra. 2019. “Time Matters: faces, externalized knowledge and transcendence,” in SOUVATZI, Stella; BAYSAL, Adnan; BAYSAL, Emma L.; Time and History in Prehistory. New York: Routledge, pp. 211-212.

Bergson will differentiate, albeit artificially, as he says, the lesson learnt, which belongs to the first memory, from each singular reading of that very lesson, which exemplifies the second memory.

BERGSON, Henri, 1911. Matter and Memory. London: George Allen and Unwin, p. 93.

Id., Ibid., p. 92.

Id., Ibid., p. 102.

Id., Ibid., p. 184.

Id., Ibid., p. 186.

DELEUZE, Gilles. 2005. Cinema 2: The time-image. New York: Continuum, pp. 78-79.

Id., Ibid., pp. 67-68.

Id., Ibid., p. 80.

“Living being is rhythmically organised, with the processes and patterns of repetitions involved differing in their recurrence, thus signifying renewal. Such renewal is not change but it constitutes time. This directional rhythmicity endows beings with memory, foresight, and the capacity for synthesis. As such, the rhythmic temporalities of growing, ageing, healing, regenerating and reproducing are all directional aspects of the dynamics of organisms with form,” Barbara Adam and Sandra Kemp, Op. cit., p. 212.

“Opening the perspectival lens to an ever-wider time frame enables us to recognise relations that are invisible from a narrower temporal frame of reference. It allows us to see the braid of connections that relates human beings to star matter,” Id., Ibid., p. 216.

“But, if we ask when consciousness is going to look for these recollection-images and these dream-images or this reverie that it evokes, according to its states, we are led back to pure virtual images of which the latter are only modes or other degrees of actualization. Just as we perceive things in the place where are, and have to place ourselves among things in order to perceive them, we go to look for recollection in the place where it is, we have to place ourselves with a leap into the past in general, into these purely virtual images which have been constantly preserved through time. It is in the past as it is in itself, as it is preserved in itself, that we go look for our dreams or our recollections, and not the opposite. It is only on this condition that the recollection-image will carry the sign of the past which distinguishes it from a different image, or the dream-image, the distinctive sign of a temporal perspective: they exhaust the sign in an original virtuality,” Gilles Deleuze, Op. cit., p. 78.

Deleuze states in relation to the novel, for example: “In the novel, it is Proust who says that time is not internal to us, but that we are internal to time, which divides itself in two, which loses itself and discovers itself in itself, which makes the present pass and the past be preserved.” Id., Ibid., p. 79.

According to the most recent research the Nebra sky disk time stems from the Iron Age. In some specialised literature, it also appears dated to the Bronze Age.

BERGSON, Henri, Op. cit., pp. 101-102.

YATES, Frances. 2014 (1966). The Art of Memory. London: The Bodley Head.

Id., Ibid., p. 25.

The Memory Room was originally conceived for the exhibition Book of Thirst (2016), in the Contemporary Gallery of Serralves Museum, curated by Ricardo Nicolau.

Shōji are sliding panels made of a wooden lattice frame over which translucent paper is glued, opaque enough to block sight but thin enough to let light in. In the traditional Japanese house, they are used in the transition between the exterior and interior spaces. They can also be combined with other types of panels, allowing for creation of different degrees (or sections, in the same plane) of transparency and opacity.

GOETHE, Johann Wolfgang von. 1840. Theory of Colours. London: John Murray, pp. 314-315.

According to the artists’ description: https://marianacalo-franciscoqueimadela.com/portfolio/animal-vegetal-mineral/

Id., Ibid.

See Francis Yates, Op. cit., pp. 124-125.

In the words of the artists themselves: https://marianacalo-franciscoqueimadela.com/portfolio/midnight/

ANDRESEN, Sophia de Mello Breyner. «Silêncio» in ANDRESEN, Sophia de Mello Breyner; Histórias da Terra e do Mar. Lisboa: Texto Editora, p. 49.

Id., Ibid., p. 51.

Id., Ibid., pp. 54-55.

DELEUZE, Gilles. Op. cit., p. 80.