The Composition of Silence

“Through an Intensive Architecture: the composition of Silence as an architectonic sensation” is a scientific paper presented at the International Symposium “The Place of Silence: Experience, Environment and Affect,” at the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, in June 2016. Silence is one of the architectural sensations that I focus on my research.

I would like to begin with an excerpt from a short story written by a Portuguese writer Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, titled “Silence” to which I will come back. This story helps us to characterise silence as a sensation with specific aesthetic qualities, which in the text are given by words and their infinite combinations into sentences, and, then, to think about silence as created by a work of architecture.

“There was a great calm. Everything was neat and the day was ready.

And Joana slowly walked across her house.

Opening and closing the doors, switching the lights on and off. The rooms disappeared in the dark and appeared from the dark in the light.

A sweet silence floated like a stretched thirst.

The silence drew the walls, covered the tables, framed the portraits. The silence sculpted the volumes, cut out the lines, deepened the spaces. Everything was plastic and vibrant, dense from the reality itself. The silence as a profound tremble roamed the house.

The known things - the wall, the door, the mirror - showed one by one its beauty and its serenity. And in the opened windows the night of June showed its constellated and suspended face.

Joana slowly walked around the room. She touched the glass, the lime, the wood. It had been a long time since each thing had found its place there. And it was as if that place, as if the relation between the table, the mirror, the door, were the expression of an order which surpassed the house.

The things seemed attentive. And the woman who had washed the dishes sought the centre of this attention. She had always sought it, but whom can capture it?

The silence was now bigger. It was like a flower that had fully blossomed and smoothed out all its petals.

And around this silence the outside night's stars turned slowly and its imperceptible movement took in itself the order and the silence of the house.

With her hands touching the white wall, Joana breathed softly. Her kingdom was there, there in the peace of nocturnal contemplation. From the order and the silence of the universe an infinite freedom rose. She breathed that freedom which was the law of her life, the aliment of her being.

The peace surrounding her was open and transparent.

The form of things was a spelling, a writing. A writing she did not understand but recognised.

She crossed the room and leaned out of the open window in front of the pure blue instant of the night.

The stars were shining, intimate and distant. And it seemed to her that between her and the house and the stars an alliance had been established since forever. It was as if the weight of her consciousness was necessary to the equilibrium of the constellations, as if an intense unity crossed the entire universe.

And she inhabited that unit, was present and alive in the relationship of things and the very attentive reality housed her in its immense and acute presence.” (1)

From the rhythm of the words, from the words themselves, the punctuation and the empty spaces that gives the text its expression, we face a growing sensation of silence. It starts as a quiet moment, serene at night, where things express their inner order and find their place. There is a comfort that one seems to find in matter while Joana crosses the several rooms of her house, touching the walls, the doors, the tables. The house is the place of silence. And silence here seems to express the tranquility that one usually finds at home. Then, the sensation of silence starts to increase. Independently of the sensation - as I will later explain - there is always a “wave” that crosses its plane of composition and creates several thresholds and intensities. When a sensation reaches its highest intensity, it changes its nature and becomes another sensation. This short story also expresses this rhythm that we find in every sensation. At the beginning, the composed silence depends on the night, on the movement of the trees, on the matter of things or spaces familiar to Joana. There isn’t any strangeness in this silence. Silence makes the presence of things alive, because it is closer to matter. Then, the silence reaches its maximum of intensity where is an unknown force that ties Joana, each part of her (it’s no longer only about the house) and the universe. Silence is the unity that can never be explained, touched or felt, and, at the same time, it is what can only be felt. It is a pure sensation. Joana recognised it, but didn’t understand. The sensation or the being of the sensible is, according to Gilles Deleuze: “the intensity, the difference within intensity, that constitutes the proper limit of sensibility. It is also the paradoxal character of this limit: it is the insensitive, that which cannot be felt, because it is every time covered by a quality which alienates it or ‘opposes’ it, distributed in a surface that reverses it and nullifies it. But otherwise, it is what can only be sensed, what defines the transcendent exercise of sensibility, since it gives to feel, and thus awakens the memory and the thinking.” (2)

© Hélène Binet. Courtesy of the artist.

More than the order between things, beings and the universe (three scales or degrees from which the sensation of silence constitutes itself in the short story), silence is the expression of freedom. At this degree and moment of the text, it seems that nothing can sully this pure silence. And it should be noticed, that in any moment of the text silence is described as absence of sounds, on the contrary, we still listen to them, but their presence imply a transformation of Joana’s body (and ours as readers) into an attentive listening where things and what unites them to the universe become more intense and alive. We can only reach this point of maximum intensity of a pure silence when we are close to the sound of things - to their matter - before their presence transforms into something unbearable for our bodies (which will then follow something outside silence).

What I’ve been exposing is explained by Deleuze (and Deleuze & Guattari) under a practice named “body without organs.” (3) The body without organs is not a concept, as some authors mention, nor it is an abstract idea either. Deleuze and Guattari are very clear: it’s a practice, a set of practices, which implies a transformation of one’s lived body into an intensive body, which means that the body is no longer defined by its physical organisation, by its organs, but by intensities, velocities and thresholds that, as the authors say, envelop a sensation (which is close to Espinosa’s definition of a body). But we should go carefully, (4) because some misunderstandings arose within this practice, as Deleuze and Guattari’s favourite examples report cases of physical bodies (sometimes even sick or drugged), like the masochist who uses his or her own body to create a plane that will only be populated by “intensities of pain, pain waves.” (5)

First, the masochist ties the body parts with elastic bands or ropes and sew the orifices turning the body into a plain surface. Then, starts the flogging through whatever means are allowed, increasing and intensifying the pain more each time. The masochist doesn’t look for pain or pleasure with it, but rather to create a sensation of pain that flows freely through the entire body, previously transformed into a surface, without any kind of obstacle or hole where the sensation of pain would vanish or decrease. (6) It’s always about how the desire itself (the plane of the body without organs is the plane of consistency of desire) is composed and through which lines does it flow uninterruptedly, enveloping and enveloped in a continuum of intensities (we must advert that it happens only on a molecular scale, within the intense matter of the unconscious).

When it comes to making a body without organs, Deleuze & Guattari define two moments: the first requires the fabrication of the plane, which usually implies an elimination of clichés as well as of all relations subject-object. (7) There’s no Self in the body without organs, only a series of becomings, as the two authors would later explain. The masochist’s body without organs, for example, is populated or crossed by a becoming-horse or a becoming-animal. The second phase happens when the intensities start to circulate in the plane, and, when a force is captured at a certain degree, compose a sensation. In the case of the masochist, the sensation of pain depends of a composition between the whip, the rhythm of the flogging, etc. The two moments happen simultaneously, otherwise the fabrication of the body without organs fails or results in an empty body without organs (which means that a sensation is not created).

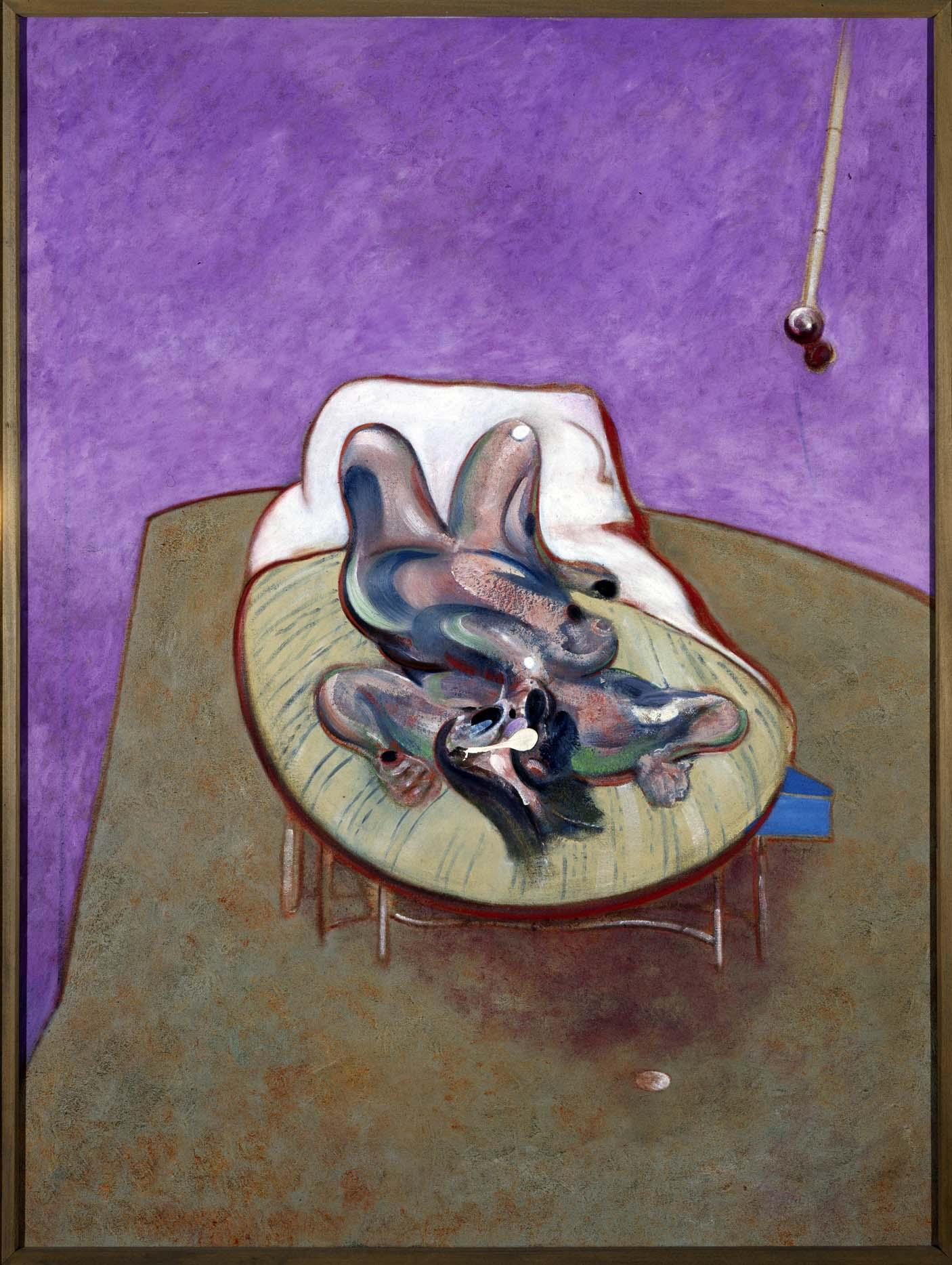

Lying Figure, Francis Bacon, 1966.

In his book about Francis Bacon, Deleuze definitely links the body without organs to the process of creation of a work of art. (8) The phases are the same as described in Mille Plateaux, but, in this book, we start to be in presence of several bodies without organs. There is Francis Bacon’s own body without organs that implies different artifices or mechanisms, from the way he uses the history of painting, for example, that help him to remove all the clichés from the canvas to his painting techniques that crystallise the different forces he imprints in his paintings, the presence of the movement of the hand, of the round gesture, and so on. But Francis Bacon’s body without organs vanishes away at the very moment the painting embodies the sensation, just like Cézanne mentioned (and Deleuze points out to this relation between the two painters), paraphrasing: the sensation is not in the air, it is in the body, even if of an apple. If successively created, the trace of the fabrication of a body without organs lives in the bodies (Figures) painted, that detain, in their turn, the power to affect us and transform our flesh and nerve into that sensation or yet another, allowing us to create a body without organs for ourselves, even without having consciousness of it. The very moment we notice, it disappears, but before we were totally immersed in the painting, and in the case of Francis Bacon’s paintings, sometimes it is when a vomit starts rising through our gullet and we are forced to look away.

It happens with the short story as well. The sensation has this power to force our body to transform itself in a plain and intense surface, where each exterior sound is metamorphosed into silence and we feel close to the things, sharing with them the same silence. The silence is thus not connected to our ears, to what we listen to, but to our body’s ability to convert itself into an attentive listening. In architecture, we also find several bodies without organs or traces. Peter Zumthor, without naming it, curiously gives the example of music: “We know all about emotional response from music. The first movement of Brahms’s viola sonata, when the viola comes in - just two-seconds and we’re there! […] I have no idea why that is so, but it’s like that with architecture, too.” (9)

The sonorous wave that affects us transforms our body into a musical plane, planting ears all through it, in our stomach, in our lung, in our breast, as, in seconds, we dissolve ourselves and become a sonorous expressive matter, become birds and the cosmos. Zumthor is correct when he says that this happens in architecture too. In certain works, our bodies are forced to wait, for example, or to inhabit space with such postures or to walk around it following movements that awake the flesh and the nerve. We may recall all those postures of the body that Adolf Loos imprints in his houses, as if the inhabitants were Beckett’s characters or Bacon’s Figures, or the movements Lewerentz obliges the body to describe in space. In certain works, there is a preparation of the body simultaneously of elimination of remains and an intensification acting upon the body (upon its flesh and nerve), transforming, finally, the lived body into an intensive body. As Deleuze remarks: the body without organs is “at the limit of the lived body, it’s the intense and intensive body.” (10)

In architecture, the inhabitant constructs a body without organs for himself or herself only if the work of architecture is a work of art that holds a block of sensations. Usually, when it comes to define architecture as art, and Loos himself denied this quality with the exception of monuments and graves, some authors immediately state that a building or an architectural space must be used by people, being its main purpose to be inhabited. Nevertheless, what type of inhabiting may occur when a work of architecture, beyond functions and types, beyond material structures and techniques, holds a block of sensations? A work of architecture, that may be consider a work of art, must create within it an interval of an intensive body-space. It’s interesting that Deleuze defines several art forms by what they create that is unique to them. For instance, painting is a block of lines and colours, cinema is a block of image-movement and image-time, music is a block of sounds… Deleuze doesn’t give any definition of architecture (although he does mention that architecture is the first art expression, and art appears with the animal when it transforms the territory into a matter of expression, into a plateau), but, taking into consideration what has been said, we may define architecture as a block of body-space, where the two terms - body and space - which define the interval, in order to architecture become a work of art, must become, in their turn, an intensive body and intensive space, both defined by the intensities that populate the interval created. A lived body that inhabits space must transform itself into an intensive body or body without organs, precisely when it inhabits an intensive space, a type of space that is defined by the sensations that is holds or creates, thankfully to its matters of expression or aesthetic composition.

In Loos’ houses, for example, we witness, almost literally, to this interval’s fabrication. First, all the clichés and symbols are removed from the plane of composition (it’s curious that Karl Krauss named Loos the architect of the tabula rasa): family, power, subjectivity were removed to give birth to a space defined only by its pure qualities. Even the program is in part eliminated in the sense that it was built up through the “elevation” of space and the modulation of volume from which the program would naturally fit (if we separate into different levels, we immediately introduce a difference in their occupation, and a movement that may be slower or faster, or constrained). Then, we assist to a clear definition of the body postures (the feminine and the masculine bodies) in space. For example, the woman’s room in Villa Müller: Mrs. Müller could choose to sit in the small sofa if early in the morning, and the light would come in from the side, creating beautiful warm reflects on the light wood panels. She’s very comfortable, seeing who might come from the entrance or from the corridor (the one that access to her husband’s room). Or she may choose to sit in the sofa placed just below the overture to the main living room and, once there, choose if she turns her back to the living room or if she prefers to keep an eye on both entries of the room. All these postures were clearly rehearsed by Loos himself, as he usually did while the construction works elapsed. And contrary to what some authors have been saying, these postures only have to do with the placement of the body in the space exactly whenever a force is exerted upon the body and a tension or a spasm is produced, coinciding, in space, with a maximum of intensity or a threshold, recalling curiously Bacon’s Figures. Passing the door, the sensation changes. All these imperceptible movements, tensions and spasms of the body in Loos’ houses depend solely of the composition of sensation which is mastered by the architect. The body enters into the plane of composition as a matter of expression, similarly to other elements. The body, its postures and declinations are part of the code of sensation, implying however an experimentation of Loos’ own body and its transformation into a body without organs, where he was able to localise the precise limits and thresholds of the sensation.

Mrs. Müller’s Room, Villa Müller, Early in the Morning, Adolf Loos, 1930.

Returning to the sensation of silence, the means through which silence is aesthetically fabricated differs significantly from one art expression to another due to their different matters of expression. However, the sensation has a direct impact on the nervous system, upon the flesh and the nerve, awakening the paths of sensibility and intuition in the body. It’s true that the artists understand this quite naturally. Louise Bourgeois used to say that “the forms if correct should have a direct impact even unconscious” (11) (an idea that she shared with Francis Bacon). Silence as a spatial sensation has thus an immediate, intuitive and instinctive effect upon the body. First, the body is obliged to silence itself to become an attentive listening, a surface where sounds reach their maximum intensity.: the 0 degree, as Deleuze says. By this time, the body becomes an intensive sonorous matter of the space, where the little sounds, that seem inaudible to the lived body, reach an intensity never obtained before, never liveable, almost unbearable. The space composes a sensation of silence when the body augments the space’s inaudible sounds, as if it were a resonance box, where sonorous waves traverse and reach unknown places in the body itself (where there will be, as Deleuze explains, temporary and provisional presence of determinate organs, temporary ears). (12) As you may remember, the author of the short story wrote that “silence drew the walls… sculpted the volumes…,” but she was enveloping all things described in the sensation of silence to make us feel it as well. In a work of architecture it’s not about how silence draw the walls, but the opposite, how the walls draw silence, how the volumes sculpt or edify silence.

I would like to go back the short story and continue with parts of it :

“It was then the scream was heard.

A long shrill scream, unbound. A scream that crossed the walls, the doors, the room, the branches of the cedar.

Joana turned at the window. There was a pause. A small immobile moment, suspended, hesitant. But soon new screams arose, piercing the night. (…) It was a woman's voice. A naked, stray, lone voice. A voice that from scream to scream was deforming, disfiguring until transforming into a howl. Hoarse and blind howl. Then the voice faded, lowered, took a sobbing rhythm, a weeping tone. But soon grew again, with fury, anger, despair, violence.

In the peace of the night, from top to bottom, the screams opened a large crack, a wound. And as the water begins to invade the dry interior when a hole is opened in the hull of a ship, that way now, through the crack the screams had opened, the terror, the disorder, the split, the panic penetrated the interior of the house, of the world, of the night. (…)

The woman could barely be seen, grabbing the wall, in the half-light, on the other side of the sidewalk. Her naked screams, close, unbound filled the penumbra. In her voice earth and life had stripped their veils, their modesty and showed their abyss, revealed their disorder, their darkness.

(…) She screamed as if she was alone in the world, as if she had surpassed all companionship and all reason and had found pure loneliness. She screamed against the walls, against the rocks, against the shadow of the night. She raised her voice as if ripping it out of the ground, as if her despair and her pain sprout from the very ground supporting her. She raised her voice as if she wanted it to reach the end of the universe and, there, touch someone, wake someone, force someone to answer. She screamed against the silence. (…)

Suddenly, she stopped (…) For some time an echo of sobs and steps fluctuated in the heavy air of the street, which moved away and diminished. Then again came silence.

An opaque and sinister silence in which the scrabbling dogs could be heard .

Joana returned to the living room. Everything now, from the fire of the star to the polished sheen of the table, had become unknown. Everything had become absurd accident, without connection, without kingdom. Things were not hers, nor were her, nor were with her. Everything had become oblivious, everything had become unrecognisable ruin.

And touching without feeling them the glass, the wood, the lime, Joana crossed her home as a foreigner.”

A crack has been opened in the middle of the silence, in the perfect unity between the body, things and the universe, caused by a scream that erupts from the darkest anguish, from absolute despair. The silence is no longer a calm silence, but indifferent. A silence that evokes the face of nothingness. This later excerpt helps to think about the composition of silence in the two further examples, because both are places where death is celebrated and where the work of architecture seems to compose an indifferent silence (in life, we’re always foreigners to the death). Therefore, the silence, that the works compose, doesn’t depend on one’s feelings (namely those of despair), nor on any subjective interpretation of another life or idilic space or garden (these feelings or thoughts belong only to the inhabitant), but only of the architectural artifices that prepare the body to become that attentive listening and, maybe there, to encounter another silence, close to the one Joana felt in the first part of the story.

Malmö Eastern Cemetery (view towards the city), Sigurd Lewerentz.

The Malmö’s Cemetery, by Sigurd Lewerentz, (13) is a huge park in the perimeter side of the city that people use as such: crossing it on foot or by bicycle, in their daily routines, in their way from home to school, from and to the city centre. The original idea of a ridge takes all the topographical predominance that Lewerentz dedicated to it. From there, we look to the city centre and all around: it’s the only moment where the presence of a life seems subtly to superimpose. On the contrary, from the paths sideways, we do not have perception of the city, but only that of a flat vast wide ground, spreading infinitely to the sides, despite the trees always demarcating the perimeter of the cemetery and an end is known. We recognise this idea from other Lewerentz’s cemeteries whenever he desired to create a peaceful, silent and inner space. In the Woodland cemetery (a project with Asplund), a transitional zone was created - a wide belt - between the surrounding area and the cemetery, in order to prepare the inhabitant before entering the space (it’s a slowing down of one’s body). (14) This interval is, in Malmö, a thickly planted allée, which helps to create an inner and solitude space. Solitude is silence’s ally, and both are given by the huge vastness of the paths and the shadow of the bushes, as in a classical order.

Malmö Eastern Cemetery, Sigurd Lewerentz.

The light, which Lewerentz worked solitarily in his Churches, it is in this open space to the sky also defined and delimited. And, as in those, it's the light that encompasses the rhythm, hence the silence becomes expressive. If we allow, we abandon ourselves hours to walk around the park, apparently immutable, and yet, its fabric never constrains a piece of ground, a bank, a bush. Indeed, it is needed a proper time to apprehend all its singularities, the time of the infinity. It recalls Lewerentz’s own long walks for hours and hours among the nature to perceive the imperceptible variations between stones and plants, tones and patterns, land and water. (15) To compose the silence implies to build the time of the infinity without any trace of melancholy. We should notice that Lewerentz pursued a pure sensation of silence which has nothing to do with the often recognisable melancholy of the cemeteries. In the sensation, there aren’t any subjective interpretations or one’s feelings, only a sensible movement in our bodies that becomes silence in pure space. This quality was recognised, for instance, by Sven Markelius in the Resurrection Chapel of the Woodland cemetery: “The sense of melancholy never becomes oppressive and the expressiveness never sentimental. The form speaks a pure language where clarity is never lost to an inarticulate murmur of mystical atmospherics.” (16) In this chapel, Lewerentz tested meticulously every single movement of the body and all its postures and spontaneous reactions (for example: the difference of light between the interior and the exterior, causing our pupils to contract (17)), intertwining with the chapel’s form and placement in the landscape. He proceeded through form, placement, the correct position of the windows to their dimensions, through materials in a way that the body becomes the plain surface where the sensation lives. He makes of the inhabitant’s body an intensive body.

Malmö Eastern Cemetery, Sigurd Lewerentz.

The composition of light is thus extremely important to compose the silence. In the churches, Lewerentz works the light punctuating the wide flat space of the assembly with beams of light. In St. Peter’s, the light comes sometimes from the side, and other times, from behind, but always from above. It is not the vastness of the gaze that imposes silence to one’s body, as in the Malmö cemetery, but the light that punctuates a place to be in silence. If we arrest ourselves looking to the exterior, we are forced to raise the face and to seek the landscape of which we only have a subtle seeming presence. We know almost nothing of what goes on out there... it's always the silence that is imposed upon our bodies. Even in St. Mark’s Church, where there are a few openings to the exterior that come to the ground, Lewerentz matched the light beams with the intervening space between the assembly and the altar, where, once again, the created abstraction imposes the body a concentration in the interior space, in the silence of the interior. And, in this sense, we may consider, even if it is an exterior space, that the Malmö Cemetery is, in fact, an interior space.

We also witness silence as a spatial sensation in the Steilneset Memorial in Vardø, by Peter Zumthor (and, in this particular work, the sensation of silence is coupled with another sensation, that of contemplation). In the composition of sensation, thresholds of intensity are determined by the action of exterior forces (once the body is already in a process of becoming). In the Vardø Memorial, these thresholds coincide with the ones of the proper building, of the entrance and the exit, as a long walk through the Northern landscape already took place (by the time we arrive at the memorial, we are totally immersed in the landscape, we are already a landscape like the animal who converts its territory into a plateau). Albeit being apparently symmetric, from whatever side we reach it, the sensation changes by the very act of opening the door and crossing the space. The entrance, independently of the side, is marked by the heavy door (understanding clearly the door as a threshold, Zumthor always pays extreme attention to the doors and all their details, from how our hand grasps the handle, to the movement that the door describes when we push it or close it, to feeling its weight or to its aesthetic expression, the texture of the materials mixed with the time of use and the time of nature…) and once we enter the dark corridor, we know that we can’t go back. So, we murmur the names (even if we don’t know how to read them, because it doesn’t matter if they are in a foreign language) to evoke their own rhythm like in a prayer. And our steps increase the silence.

The Memorial rests alone in the middle of the Northern Artic Landscape, under the strong effects of nature, where the land ends, and we feel so strongly nature’s power. Once inside the Memorial, the atmosphere is more silent, but it is also of concentration, of pure saturation (given mainly by the black canvas, an artifice that Zumthor would create again in the Summer Serpentine Pavilion, and, in some former projects, we may identify in the double wall or corridor that envelops space to prepare the body before inhabiting). The silence, however, only becomes expressive, because Zumthor kept the presence of the nature elements inside the tunnel. We hear and feel the wind, the Arctic's icy cold, the cries of the seagulls and the birds flying in circles. The tunnel is crossed by the nature, by all its elements, remembering us of the house of The Sacrifice, by Tarkovsky, which stands in that precise limit of a strong landscape that traverses the house, submitting it to its elements. The Memorial is not a building standing freely in the middle of the landscape, but it’s itself a landscape (a plateau, in the deleuzian sense). And just like the Malmö cemetery, it’s a silent landscape. Both expand, dilate the landscape they envelop, increasing the subtle sounds of the trees, of the wind, of the steps that they all produce in the pure air. This dichotomy between exterior and interior space is thus extremely important in the composition of silence as a spatial sensation. Lewerentz turns the exterior space of the cemetery into an interior space, imposing silence upon our bodies and minds, whereas Zumthor evokes all the exterior forces into the interior of the tunnel, as if in John Cage’s piece: all the subtle differences of sound in the interior increase the attentive listening of our bodies. (18)

Malmö Eastern Cemetery, Sigurd Lewerentz.

The composition of sensation is a problem common to all arts, albeit each one proceeding through its proper means and its expressive matters, through colours and lines, sounds and words, stones and bricks. But once a sensation is composed, the universe and the cosmos (paying a tribute to Klee) are evoked and all its forces inscribed in our bodies. The problem of an intensive architecture deals not only with the problematic relation between art and architecture, but above all it approaches us of that interval of an intensive body-space, if we dare to stay there… The effects may be devastating, and as Joana, we may end crossing our house like foreigners.

Notes

Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, “Silêncio.” In Andresen, Sophia de Mello Breyner; Histórias da Terra e do Mar. Lisboa: Texto Editora, 1990, pp. 47-55. Translation by the author.

“C’est l’intensité, la différence dans l’intensité, qui constitue la limite propre de la sensibilité. Aussi a-t-elle le caractère paradoxal de cette limite: elle est l’insensible, ce qui ne peut pas être senti, parce qu’elle est toujours recouverte par une qualité qui l’aliène ou qui la ‘contrarie’, distribuée dans une étendue qui la renverse et qui l’annule. Mais d’une autre manière, elle est ce qui ne peut être que senti, ce qui définit l’exercice transcendant de la sensibilité, puisqu’elle donne à sentir, et par là éveille la mémoire et force la pensée. Saisir l’intensité indépendamment de l’étendue ou avant la qualité dans lesquelles elle se développe, tel est l’objet d’une distorsion des sens. Une pédagogie de sens est tournée vers ce but, et fait partie intégrante du ‘transcendantalisme’. Des expériences pharmacodynamiques, ou des expériences physiques comme celles du vertige, s’en approchent: elles nous révèlent cette différence en soi, cette profondeur en soi, cette intensité en soi au moment originel où elle n’est plus qualifiée ni étendue. Alors le caractère déchirant de l’intensité, si faible en soit le degré, lui restitue son vrai sens: non pas anticipation de la perception, mais limite propre de la sensibilité du point de vue d’un exercice transcendant,” Gilles Deleuze, Différence et répétition, p. 305.

The body without organs is a deleuzian practice upon the body. It’s an experimentation that every person undertakes whenever he or she desires and the unconscious begins to work and the body and its organs discover their own power to create sensation after their intense matter. As explained: “At any rate, you have one (or several). It’s not so much that it preexists or comes ready-made, although in certain respects it is preexistent. At any rate, you make one, you can’t desire without making one. And it awaits you; it is an inevitable exercise or experimentation, already accomplished the moment you undertake it, unaccomplished as long as you don’t. This is not reassuring, because you can botch it. Or it can be terrifying, and lead you to your death. […] It is not at all a notion or a concept but a practice, a set of practices,” Deleuze & Guattari, Capitalism and Schizophrenia: A Thousand Plateaus, p. 166 (New York: Continuum, Translation by Brian Massumi, 2004). Note: In the present paper, we use this edition, because it’s translated into English by Brian Massumi, a known deleuzian, although our interpretations and knowledge come from the original text in French, which obviously is more precise.

It would be impossible here to detail all the different implications that come from the problem of the body without organs in Deleuze’s own plane of immanence (or body without organs), and then in architecture. We may recommend the reading of: Susana Ventura, O corpo sem órgãos da arquitectura (Architecture’s body without organs). Lisboa: Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Tese de Doutoramento em Filosofia, especialidade de Estética (PhD’s thesis in Philosophy - Aesthetics), Novembro 2012 (only available in Portuguese).

Gilles Deleuze & Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus. p. 168.

“A BwO is made in such a way that it can be occupied, populated only by intensities. Only intensities pass and circulate. […] The BwO causes intensities to pass; it produces them in a spatium that is itself intensive, lacking extension. It is not space, nor is it in space; it is matter that occupies space to a given degree - to the degree corresponding to the intensities produced. […] That is why we treat the BwO as the full egg before the extension of the organism and the organisation of the organs, before the formation of the strata; as the intense egg defined by axes and vectors, gradients and thresholds, by dynamic tendencies involving energy transformation and kinematic movements involving group displacement, by migrations: all independent of accessory forms because the organs appear and function here only as pure intensities,” Idem, Ibidem, pp. 169-170.

“The BwO is what remains when you take everything away. What you take away is precisely the phantasy, and significances and subjectifications as a whole,” Idem, Ibidem. This finds its equal in Loos’ approach to architecture: remove all ornament, remove all sentiments, remove the Family (as institution), the suicide note of the girl in the chest of drawers doesn’t have anything to do with the walls (designed by the architect).

The body without organs disappears from the pages of Qu’est-ce que la Philosophie? when Deleuze & Guattari write about the plane of composition in art. It’s long known that some concepts were more of Deleuze and others of Guattari, as we also find Guattari’s doubts about the practice of the body without organs in his notes to Anti-Oedipe (Félix Guattari, Écrits pour L’Anti-Oedipe. Paris: Lignes Manifeste, 2004). In fact, the first known appearance of the body without organs (which is named after Artaud) is in Deleuze’s work Logique du Sens (1969). Then, it appears in both volumes of Capitalisme et Schizophrénie, and, finally, in Francis Bacon: la logique de la sensation (of course, it also appears in several essays by Deleuze). We only may speculate about its removal from the plane of composition in Qu’est-ce que la Philosophie?, but it immediately reappears in Francis Bacon, the major work of Deleuze on Aesthetics.

Peter Zumthor, Atmospheres. Basel, Boston, Berlin: Wirkhäuser - Publishers for Architecture, 2006, p. 13.

Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon: the logic of sensation, p. 44. It’s at this time that Deleuze criticises the phenomenological hypothesis as “it merely evokes the lived body. But the lived body is still a paltry thing in comparison with a more profound and almost unlovable Power [Puissance],” Idem, Ibidem.

Louise Bourgeois, Destruction of the Father / Reconstruction of the father: writings and interviews 1923-1997, p. 75.

For the complete series of the body without organs, see Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon…, pp. 47-48.

Sigurd Lewerentz spent his lifetime trying to compose silence in his works. It was also his way of working to bring forth to the best composition. “Lewerentz chose silence over speech, and in this manner a mystical darkness arose around him,” says Janne Ahlin (Janne Ahlin, Sigurd Lewerentz, architect: 1885-1975, p. 12). For him, “It was a matter of listening to himself, and once he had decided, his decision had the quality of uncompromising truth.” Sigurd Lewerentz knew, without doubt, how to make a body without organs for him. As Janne Ahlin describes his way of working: “Lonely evenings and nights were Lewerentz’ most rewarding hours. No one disturbed him, the telephone was silent, and there was nobody to watch how he worked. Thus he avoided embarrassment should someone happen to discover how arduous and difficult it really was to bring forth a design, and how deep the darkness in which he groped before clarity was reached. It was as if each time the thing had to be tested to its utmost depth in order to re-emerge in a new and sharper guise. It was as if he knew that if he searched long enough in the darkness it would in time lead him back again” (Idem, Ibidem, p. 11). It’s a question of creating a plane of composition dissolving all the remains, everything that could perturb Lewerentz from reaching the totally darkness. The darkness and the loneliness were therefore his artifices to totally reach silence as a sensation, crossing the plane of composition and the final work of architecture that is, in its turn, composed in that very plane. He definitely knew what allowed him to obtain the clarity in composition (the pure sensation), without anything to blur the sensation in space. He knew, just like the masochist, the artifices he needed in order to compose his body without organs.

Janne Ahlin describes this intention from a Woodland cemetery’s sketch found in Lewerentz’ archives: “Beyond the wall a 30 meter wide space was reserved as a park belt. This was possible since the land around the cemetery had not yet been built upon. The belt was to serve as a transition zone between the Woodland cemetery proper and the surrounding landscape, which was under cultivation. It was meant to visually and emotionally prepare the visitor before entry into the actual cemetery,” Idem, Ibidem, p. 42.

“Moss and stones, water plans, and the movements of waves would capture his attention for hours”, Janne Ahlin, Op. Cit, p. 11. “He studied nature’s details: the water, the plants, the stones, the play between land and water, the worn tones of umber and ochre of the rocks and the wind-swept vegetation,” Idem, Ibidem, p. 99.

Sven Markelius apud Janne Ahlin, Op. Cit., p. 77.

As the movement is described by Janne Ahlin: “The result was that he placed the chapel perpendicular to the way of the Seven Wells. He used the portico as a terminus [Lewerentz’ use of the membrane or interval to control a sensation to its point of maximum intensity], thus defining the goal of the way of the Seven Wells. The mourners would wait along the shaded northern side. They were then led in through the portal turning their attention to the East, toward the sunrise. At the ceremony’s end they would go out through a low door which opened up on the landscape to the West. Here the ground was sculpted out to a lower level and the pine trees were sparse. Light flooded in, the field of vision was opened out and one’s pupils would contract,” Janne Ahlin, Op. Cit. p. 82 (our comments in brackets).

When drawing the thermal baths in Vals, Zumthor would compare its plan to a score by Cage. Although it may reveal an intention - and Zumthor always said that the project of Vals is about a resonant stone - it maintains the idea in a single plane, the plane of comparison. In the Vardø Memorial, Zumthor apprehends the Cage’s artifice in order to transform the silence into an expressive matter of space. Zumthor has thus a fulcral relation with music. Early in the morning, it’s common to find him with the music loud, filling the entire space of his studio, while he is drawing or painting… And one may immediately notice if the drawing is flowing as he is totally absorbed into the movements of the music. (Note: the author did part of her PhD research at Peter Zumthor’s studio for two months observing, talking, researching into the archives…)